Fish Out of Water

As the lobster capital of the U.S. looks to diversify its commercial fishing industry, new options for harvesting seafood are emerging — in ocean-based farms, in cold rivers and even on land. Maine is diving into aquaculture.

Independent fishermen, the backbone of the Maine commercial seafood industry, play a vital role in the state’s culture and economy. Roughly 5,000 lobster fishermen produce 80 percent of the value of Maine’s commercial seafood catch – an estimated contribution of more than $1 billion to the state economy. But relying too much on any one species could put the state in a precarious position. The volume and value of Maine lobster fell more than 15 percent from 2016 to 2017, from $533 million in 2016 to $434 million in 2017. Tariffs imposed in July 2018 by China on select American products, including lobster, represent a new factor that could affect Maine lobstermen this year, despite a very productive season so far.

Climate change is another problem. The Gulf of Maine Research Institute (GMRI) has identified the waters off of coastal Maine as “one of the fastest-warming ocean ecosystems on the planet.” The volatility of the water temperature is just one reason many small fishermen began to focus primarily on lobster, where prior generations made a living on a varied catch. In this new reality, re-diversifying production and having more direct control over cultivation will help sustain Maine’s commercial seafood industry. Two aquaculture endeavors now in development represent decidedly different alternatives for America’s lobster capital.

The Rise of Aquaculture Worldwide

Aquaculture in Maine has been practiced since at least the 1800s. While laws regarding fish and shellfish culture date back to 1905, the Maine Legislature only began to regulate aquaculture as an industry in 1973. In the last few decades, Maine-based institutions have dived into aquaculture research, but many questions remain about how to make production more cost-efficient. Farmers bringing product to market also play an important role in determining aquaculture’s viability: by finding ways to integrate into existing supply chains or to create new ones and by understanding how consumers relate to new products, including their willingness to pay to them.

Worldwide, consumers seem very willing to pay for farmed fish. According to the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), global per-capita fish consumption is on the rise. As of 2016, aquaculture accounted for 47 percent of all fish consumed as food. Further, the first-sale value of all aquaculture production was estimated at $243.5 billion — almost double the value of global fishery production. Investors have noticed. Venture capital and private-equity capital from the same entrepreneurial ecosystems that have long funded tech startups are turning to food systems ventures.

“Fish is the new beef,” says Mike Velings, a Dutch venture capitalist and founder of Aqua-Spark, the first aquaculture investment fund. His 2015 TED talk, “The Case for Fish Farming,” has been viewed more than a million times. In light of this global surge in aquaculture, Maine’s fishing industry is exploring ways to move beyond lobsters.

What is Aquaculture?

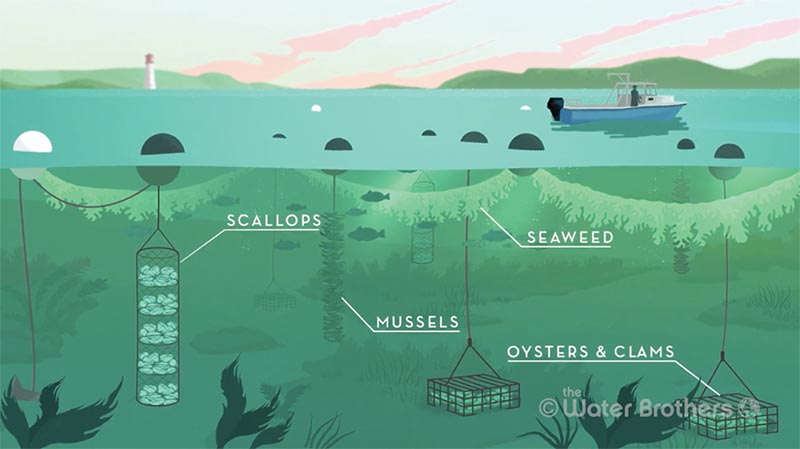

The term aquaculture refers to the farming of aquatic organisms in water and can include finfish, shellfish, crustaceans, sea cucumber, seaweed, kelp, algae — anything that grows in water. It’s related to hydroponics, which generally refers to growing plants in nutrient-rich water, without soil, as well as aquaponics, the symbiotic cultivation of plants and aquatic animals in a recirculating environment. Aquaculture differs from conventional fishing or even harvesting of shellfish and seaweed in that it explicitly includes propagation (almost always in a land-based, lab-like setting, or “hatchery”) as well as tending to the crop, or stock, through the whole growth cycle. Vertical ocean farming is essentially an aquaponic practice in an ocean environment, in which seaweed and shellfish farms are vertically arranged in the water column, mimicking the arrangement of natural systems and promoting interactivity with other ocean species around them.

All Eyes on Scallops

Tenants Harbor in St. George is a picturesque spot in Maine’s mid-coast region, nestled between two hillsides that protect it from the winds off the bay. I’ve come here to meet Ryan McPherson, Merritt Carey and Peter Miller, members of the newly formed Maine Aquaculture Co-op. The topic: sea-scallop farming in Penobscot Bay. It’s a new idea for a region more associated with lobsters, and the hope is to reintroduce a measure of diversification for independent fishermen so they can continue to make a living from the sea.

“It’s all about local knowledge,” Miller, a fourth-generation fisherman, says. “I want every young fisherman to have the chance that I had.”

Maine isn’t new to scallop production, but its cold ocean temperatures mean they grow slowly. “To harvest wild scallops in Maine, they have to be four inches, which takes about four years,” McPherson explains. “The product we’re landing doesn’t have those restrictions, because we’re growing them.”

A former fisherman with a degree in entrepreneurship, McPherson purchased Glidden Point Oysters in Edgecomb, Maine, with leases in the deep water of the Damariscotta River, in 2017. He has quickly made inroads in the state, expanding relationships with chefs and maintaining Glidden Point Oysters as a premium product, a philosophy he brought to his involvement with the Maine Aquaculture Co-op. In addition to making chefs aware of the co-op, he fostered a tie to Island Creek Oysters, which provides a robust point-of-sale and distribution network for products that share Island Creek Oysters’ emphasis on celebrating American merroir. The co-op’s first live, whole scallops — not just the abductor muscle that most people traditionally think of as a scallop — started selling on the platform in early 2018.

“Before we pull them out of the water, they are already sold,” McPherson says. Literally pulling them out of the water is interesting, too. As the net emerges from the water, the petite scallops respond to the change in their environment and clap their shells shut in unison.

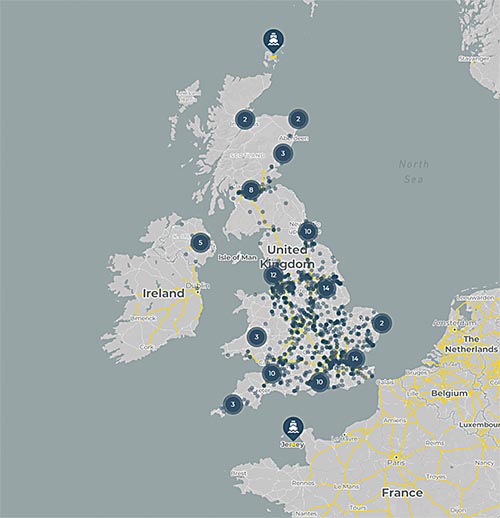

A 2016 market analysis for Maine-farmed shellfish confirmed that the portion of shellfish produced by aquaculture in Maine remains quite small — less than 1 percent of the landed value of oysters, mussels and scallops in the United States. Despite the small quantity, Maine scallops garner the highest price per pound of any state. Yet Maine produces only 2 percent of the country’s volume. To meet consumer demand, the United States imports 40 million pounds of scallop meat, with a value ($350 million) close to the value of scallops it produces domestically ($380 million). Projections about future consumer demand may be conservative because they don’t consider the impact of expanding direct-to-consumer buying options and prepared meal kits. The report also notes that Maine has the cold, clean waters to support shellfish aquaculture expansion, with projected acreage needed by 2030 estimated to be less than .3 percent of state waters.

Merritt Carey pulls a lantern net out of the water to reveal juvenile scallops in an early stage of growth. Photo by Laurie Zapalac.

Merroir

Merroir

like the French terroir, which refers to the flavor notes a wine gets from the grapes’ soil and growing region, merroir describes the way seafoods reflect the taste of the waters in which they’re grown.

Ryan McPherson explains the staging float and its relationship to the leases held by the Maine Aquaculture Co-op farther out in Penobscot Bay. Photo by Laurie Zapalac.

Juvenile scallops grow in vertical “lantern nets” (left), a Japanese aquaculture technique adopted by some Maine scallop farmers. Once they’re larger, the scallops are drilled and hung on long lines in water 25 feet deep, where they grow to full size. Click image to enlarge. Image courtesy the Water Brothers.

For delicious scallop pics and shots of the sea farmers at work, follow @MaineAquacultureCoop on Instagram.

For delicious scallop pics and shots of the sea farmers at work, follow @MaineAquacultureCoop on Instagram.

The Salmon Story

Maine’s wild Atlantic salmon population hovers on the brink of extension due to loss of fresh water spawning habitat, overfishing, pollution and other forces. Heavily depleted by the late 1960s and declared an endangered species in 2000, wild Atlantic salmon is no longer fished commercially in Maine waters. In 2016, habitat restoration projects began, and small upticks in population are now being recorded.

Responding to the vast U.S. market hungry for salmon, Norwegian investors are focusing on Maine for land-based production. The U.S. exports the majority of the seafood it harvests, while importing species such as salmon — an inefficient crossover that generates heavy carbon dioxide emissions. But salmon farmed in Maine can efficiently reach more than 50 million people in adjacent states, a “grow-local” solution.

“The exciting thing is, you can place production close to the consumer,” says Erik Heim, CEO of Nordic AquaFarms. “So instead of airfreighting in tons of salmon from New Zealand, Chile, Norway, Scotland, you can produce it locally.”

Moving Indoors

Nordic AquaFarms aims to produce 30,000 metric tons (approximately 66 million pounds) of salmon annually in a facility in Belfast, Maine, estimated to cost $500 million when fully complete. Due in part to concerns associated with ocean-based finfish farming, including fish feed sourcing, disease, use of antibiotics, fish escape, pollution and others, the location of aquaculture is changing dramatically. Earlier aquaculture practices for finfish entailed producing eggs and growing juvenile fish in land-based hatcheries, then releasing them into sea-pens — or in the case of stock regulation, into the wild. Today’s finfish aquaculture is increasingly keeping the fish indoors for life.

Heim explains that the facility will comprise three main production areas: hatchery, grow out and processing. The facility’s engine is a recirculating aquaculture system (RAS). “Land-based farming is basically where everything is happening indoors,” Heim says. “You’re taking water in and releasing water out, so you can clean it and treat it,” a practice that allows for recirculation and a reduction in overall water usage and nutrient discharge. “That’s a key part of the concept.”

Overhead rendering of Nordic Aquafarms’s site in Belfast, Maine. The first phase of construction of the indoor-salmon-farming facility is projected to be complete in 2020 or 2021. Image courtesy Nordic Farms.

Deploying aquaculture on a large scale indoors means confronting questions about selective breeding, genetic engineering, use of fertilizers and antibiotics, and waste processing — issues familiar to other types of industrial-scale land-based farming. Another question is how the introduction of foreign-investor-driven projects will impact the local communities and economies that host them. While operations of this size should mean more jobs, fishermen may have to adjust to harvesting their catch on land.

While building on decades of knowledge, Nordic AquaFarms operations are relatively new. Founded in 2014, its business units include Sashimi Royal in Hanstholm, Denmark, the largest yellowtail kingfish facility in the world, which began producing commercially in early 2018; and Fredrikstad Seafood in Fredrikstad, Norway, which will be the biggest salmon facility in Europe when it comes online in 2018. The Fredrikstad operation is “the blueprint for what we’re doing here. What we’re looking to do is not just build a land-based facility. We want to change this industry, and we’ve invested a lot into innovation,” Heim says. “We’re taking the science to an entirely new level.”

This raises an important question: How can radically new practices — so new they aim to be innovative on a global scale — be embraced by communities devoted to traditional methods?

Heim takes a stab at the answer. “If you look at the Maine seafood industry, it is very fragmented, many small producers, mostly concerned about their own business. Enormous resources go into building seafood brands and salmon brands in Norway. I think there is an opportunity for the industry (in Maine) to get together and do more.”

Yet, Maine is a vastly different place politically, socially and economically than Norway. Rather than solely focusing on exporting Nordic best practices, what will the Norwegians seek to learn from Mainers, ensuring that knowledge sharing is a two-way process? And how will they address concerns raised by their host community: What does releasing waste and nutrients a mile off shore really mean? How will it affect the bay? How will it affect me as a swimmer? How many people do you intend to employ and how much will you pay them?

On the Dinner Table

Land-based salmon farming and ocean-based scallop farming operate under wildly different assumptions about how people acclimate to new ideas, from winning over potential consumers to gaining support from host communities and existing players in the commercial seafood industry. Each presents a distinct set of questions about the impact on the state’s environmental resources. Each relies on and will amplify different industry knowledge. Can Maine go forward in a way that its land- and sea-based farming industries not only limit negative impacts for each other, but also find opportunities for knowledge sharing and mutual benefit?

Returning home to Boston, I find a flyer in the mail from the meal kit delivery company HomeChef, showing whole carrots, enticing bok choy and two precisely cut salmon filets. It reads, “Designed with you in mind, using fresh, thoughtfully sourced ingredients.” As food production and consumption continue to evolve, it still remains up to us to decide what exactly “thoughtfully sourced” means.

Learn more about vertical ocean farming in this TED article.

Learn more about vertical ocean farming in this TED article.

Books

Books

Podcasts

Podcasts

Film/TV

Film/TV