The Evolution of How We Shop for Food

In 1900, the “eat local” movement wasn’t a movement — it was harsh reality. Just over a century later, advances in technology — from shipping to inventory management — allow us not only to eat Japanese sushi so fresh it’s practically flapping, but also to restock our fridge with delivered groceries we ordered two hours before. How did our food get here?

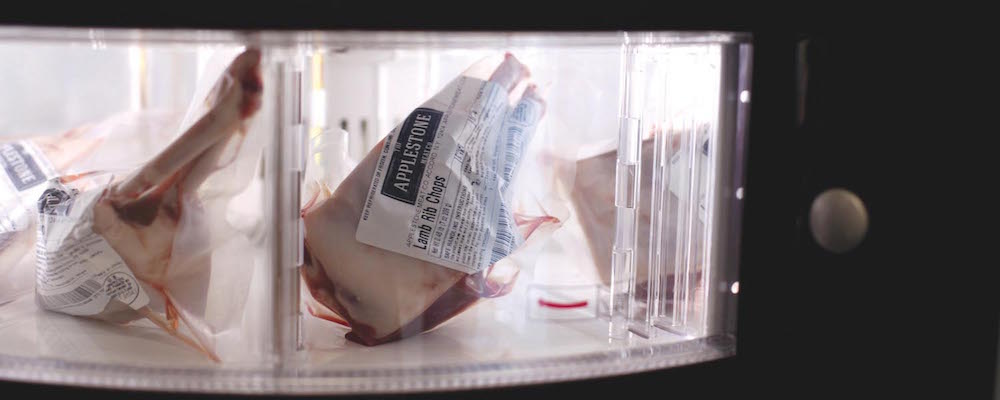

Located in a gritty section of Manhattan called Hell’s Kitchen is a large grocery store stocked with everyday essentials — but it’s not open to the public. The building is leased by Fresh Direct, the largest online grocer in the northeast; it’s part of a new hybrid of on-demand shopping and is called a “dark store.” Products on the shelf of a dark store are picked and packed by employees and sent off in cars or on bicycles to fulfill same-day deliveries. In today’s grocery store parlance, same-day has ousted Fed-Ex priority overnight as the new gold standard.

For FreshDirect, creating a new sub-brand to serve consumers’ last-minute needs was vital to remaining competitive. The idea was tossed around in 2011, when the team did a market assessment of its conventional model. Online grocery stores offered a wide spectrum of where and when you get your food. But if you needed something the same day — maybe because you hadn’t thought about dinner or you didn’t know where you would be — well, you were high and dry. The resulting concept, named Foodkick, launched first in Brooklyn in November 2015 and then in Manhattan in 2017.

The private company won’t share numbers, but Jason Lepes, vice president of merchandising, says they’ll be expanding to a third location soon.

“The business is going really well,” he says. “Huge.” FreshDirect is not alone. A McKinsey & Company report on the state of parcel delivery notes: “The last mile is seeing disruption from new business models that address customer demand for ever-faster delivery.”

While speedy delivery is what everyone says they want, consumers are mostly interested in the cheapest option. What will bring down the cost of same-day delivery? Scale, automation and robots.

The Roots of Food Shopping

How did we get here? While today’s passionate consumers debate the merits of local versus organic, in the early 1900s everything was local. Markets were small areas where carts, farmers, buyers and sellers gathered together to buy, sell and trade. In cities, if you couldn’t pick it up within a 10-minute walk from your home, it wasn’t in your bag. Markets were open six days a week, and notions like refrigeration were pure space-travel fantasy.

Eventually, these loose outdoor areas moved under roofs and inside buildings to create permanent spaces for vendors, which enabled more reliable sourcing and a greater selection of foods offered. Over time, improvements in transportation and shipping also increased selection.

Before cars overhauled our diet — allowing consumers the ability to drive longer distances to stores and buy more than one could carry home by hand — trains did. First, by moving commodities around the country, increasing selections and lowering prices at markets. And then, by incorporating refrigeration technology.

“The refrigerated rail car made meat affordable for average households by allowing companies to ship carcasses rather than live animals across the country,” writes Marc Levinson in “The Box,” his book about the shipping industry. Once refrigeration became an everyday reality, food products could be shipped farther from their origin. [Learn more about the importance of refrigeration in the food supply chain in our feature story, “Transcending Seasons: Following the Global Cold Chain.”]

But before shipping could become fully globalized, our food cargo had to transition from rails to trucks, a trend that began in the 1940s and firmly took hold in the 1950s.

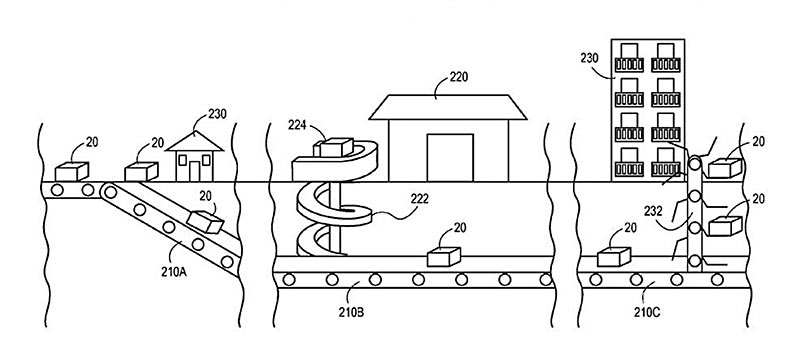

Once trucking became the de facto interstate transit (complementing trains but surpassing them in goods delivered), leaders in the industry began retrofitting the human side of delivery, tackling shipyards first. Trucking magnate Malcom McLean realized that quicker loading times could improve every stage of logistics. He helped create a streamlined container, leveraging what he knew of trucks and trains. This shipping container became the industry standard and rapidly made delivering goods by boat an affordable idea. In the 1960s, once mechanical cranes transformed how containers were loaded and unloaded, removing traditional dockworkers from the process almost completely, goods from every continent, such as kiwis from New Zealand, Italy or China, could reach the world.

Read our story about early NYC’s network of markets, located so people could access provisions as part of their daily routines.

Read our story about early NYC’s network of markets, located so people could access provisions as part of their daily routines.

Global Goods

Each year, 817 million tons of foods are shipped around the world, with distances increasing over the last 50 years to an average of 1,300 miles. More than $50 billion worth of goods is moved every day by cars and trucks, a journey that depends on shipping containers. We need look no farther than our morning cup of coffee for an illustration of those miles.

“By the time you enjoy the beans back in L.A., they had traveled more than 30,000 miles from field to exporter to port to factory to distribution center to store to my house — more than enough to circumnavigate the globe,” writes Edward Humes in “Door to Door.” “Thousands of man-hours and billions of dollars in technology and infrastructure — along with the efforts of countless unsung heroes who pack, lift, load and drive and track it all — combined to bring that cup of coffee to my lips.”

Fast Versus Instant

Ten years ago, the Natural Resources Defense Council reported that a “typical American-prepared meal contains ingredients from at least five countries outside the United States.” What’s in our refrigerator today represents an even bigger diversity, and the last mile these far-flung foods travel is being compressed into a sandwich of instantaneous desire.

While many companies and startups are focusing on speeding up the last mile, only a fraction of consumers are ready for it. In a survey of almost 5,000 people, McKinsey reported that only 23 percent wanted to pay for the same-day option. Despite that, “same-day and instant delivery will likely reach a combined share of 15 percent of the market by 2020,” McKinsey asserts.

Evidence of this burgeoning trend is everywhere: Amazon expanded its same-day delivery service to Prime members in 8,000 cities in early 2018. Around the same time, Target purchased Shipt, which has more than 20,000 personal shoppers, for $550 million. Instacart, which works with almost every major supermarket, has expanded to 69 regions across the U.S. and by the end of 2017 was serving 60 percent of American homes. Jet.com, owned by Walmart Inc., offers its same-day service for free, and soon, Walmart will pilot the same service in New York.

While everyone from big brands to startups attempts to tackle the challenges of same-day food logistics — a problem that involves route optimization, staffing, merchandising, scheduling and supply chain — the concept still relies on old-world delivery methods like trains, trucks and ships. Whoever dramatically changes that network — getting food delivered to our homes in game-changing ways — will also own that well-worn cliché: I reinvented the wheel.

Don’t be surprised when you begin to notice your sidewalk cluttered with electronics instead of people. DoorDash, an on-demand food delivery service based in San Francisco, is testing out robots as an addition to its food-delivery workforce. [Read more about DoorDash in our story, “

Don’t be surprised when you begin to notice your sidewalk cluttered with electronics instead of people. DoorDash, an on-demand food delivery service based in San Francisco, is testing out robots as an addition to its food-delivery workforce. [Read more about DoorDash in our story, “

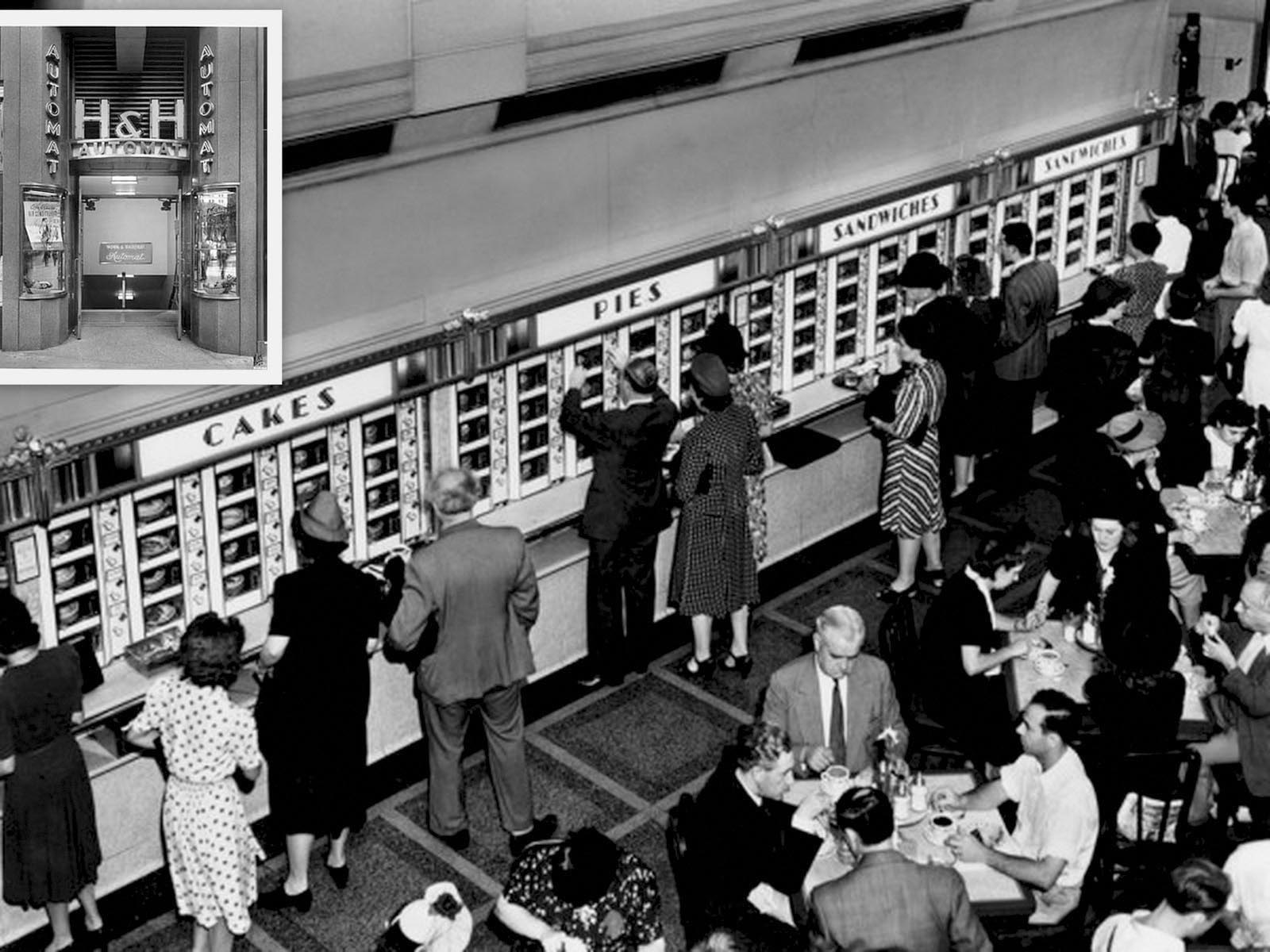

There’s going to be an Automat movie! Keep up with the film’s progress at

There’s going to be an Automat movie! Keep up with the film’s progress at