Edible Bugs: More Than Just Protein

Flavor notes range from peppery lemon to pine-nutty to prosciutto-savory. Some varieties make for lovely garnishes on your seafood salad, while others are perfect as the heart of a well-salsa’d taco.

Some new-ancient legume? The latest grain-based trend? No — I’m talking about edible bugs.

And I’m not the only one. Bug-based recipes are showing up all over Instagram and your favorite cooking magazines. Yet while we in the West are playing catch-up, some cultures around the world have been enjoying arthropods and mealworms for millennia.

If you think about it — with a wide-open mind — bugs aren’t all that different from crustaceans. After all, crayfish (or, crawfish) are known by some in Louisiana as mudbugs. Just as we enjoy the sweet flavor of shrimp and the slight crunch involved in devouring a crab or lobster, eating bugs just takes a bit of practice.

That’s what Aly Moore believes, anyway. Her site (eatbugsevents.com) and beautiful Instagram feed (@bugible) are dedicated to making bugs seem like the white-hot snack trend you’re dying to try. She even does bug-and-wine pairings to highlight the wide variety of flavor notes. And, who knows, maybe the wine helps reduce inhibitions against taking that first bite.

Top: Mealworms and dark chocolate — bugs can satisfy a sweet tooth! Photo by Ashley Corbin-Teich. Bottom: Summer salad with chickpeas, pumpkin seeds and roasted crickets from Entomo Farms.

Bugs Around the World

While eating bugs may be a novel idea for Americans and other Westerners, insects have long been a valuable ingredient in many parts of the world.

Oaxaca

grasshoppers (chapulines)

Cambodia

ants

China

crickets served instead of bar nuts

South Korea

silkworm pupae

South Africa

mopane worm

France

escargot (technically a mollusk, but they do live in the garden)

“I think people are all really pleasantly surprised,” she says about guests at her bug dinners and wine-and-bug pairing events. “I give people a spiel that does everything from comparing bugs to seafood to describing the tasting notes, and you can see them starting to warm up to the idea. That lightbulb moment is great, when they realize bugs are not at all bad. In fact, they have a familiar flavor.”

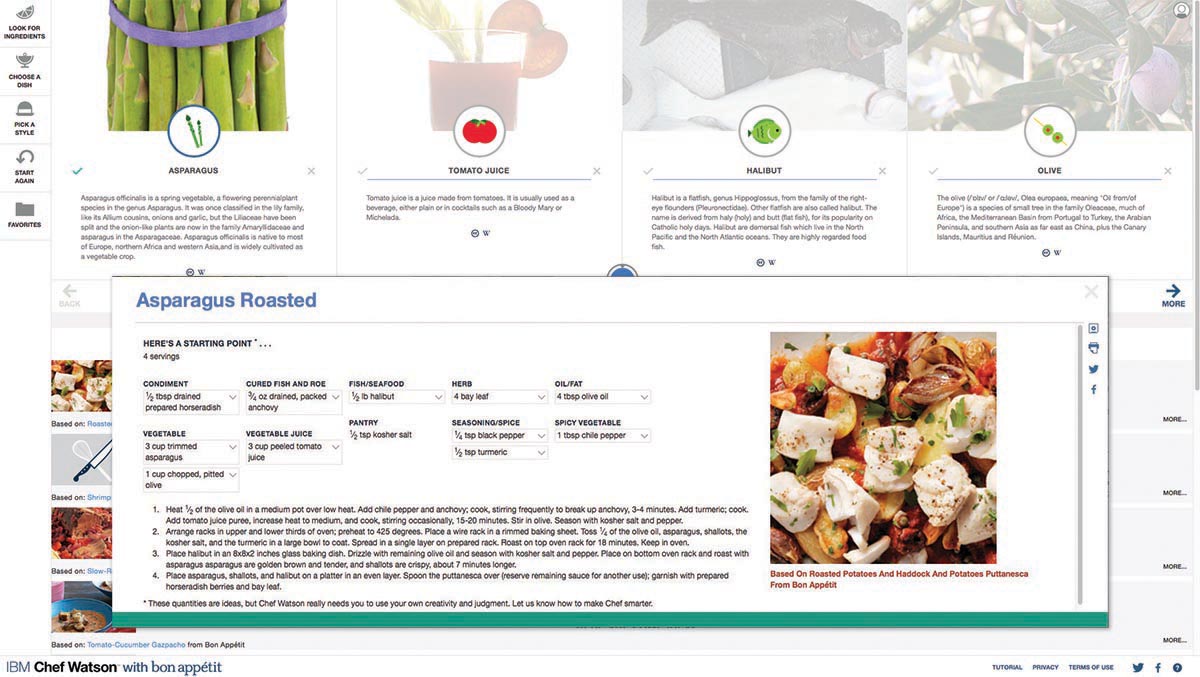

Focusing on flavor is a key tactic for Moore — especially in her wine events, where she highlights specific bug flavor notes and pairs a complementary wine. Crickets go nicely with lighter reds like pinot noir, Moore says, while meatier-flavored grubs want a more robust Zinfandel. Scorpions, you might be surprised to learn, have a delicate salmon-y flavor that’s perfect with a zingy sauvignon blanc.

If you’re not ready to take the plunge with a whole roasted tarantula, there are lots of ways to experiment with eating bugs without knowing they’re an ingredient — for example, cricket- flour protein bars or chips are increasingly easy to find in mainstream grocery stores.

But, really, Moore is a fan of highlighting the whole insect in all its glory to help people begin to think of them as a tasty option in their everyday diets.

“Comfort foods” — like pizza topped with meaty grasshoppers (aka chapulines in Oaxaca) or sago grubs, which are known as the bacon of the bug world — “are a great way to help people get over the hurdle,” Moore says. “Making comfort foods that people can relate to helps create positive associations with eating bugs.”

Pinot noir and crickets, a classic combo. Focusing on flavor is a key tactic for Aly Moore — especially in her wine events, where she highlights specific bug flavor notes and pairs a complementary wine.

Ready to start cooking with edible bugs? Check out the “Buy Bugs” link on eatbugsevents.com for resource ideas.

Ready to start cooking with edible bugs? Check out the “Buy Bugs” link on eatbugsevents.com for resource ideas.

RECIPE NOTE

How do you go from crawling to crunchy without the use of toxic pesticides or a dramatic SQUISH? Oh, just chill — the bugs, that is. While many studies concur that bugs’ central nervous systems aren’t complex enough to feel pain, you might worry a bit anyway. A humane and simple way to corral those critters is to refrigerate them. Because they’re cold-blooded, they fall asleep, at which point you can move them to a freezer to ensure they’ll never crawl, jump or fly again.