Startup Spotlight: FENIK

Originally known as Evaptainers, Fenik started out as a student project at MIT. The team’s goal was to develop a low-cost method for preserving fruits and vegetables in remote areas. Five years and many prototypes later, Fenik recently wrapped up a successful Kickstarter campaign and launched production of its Yuma No-Ice Cooler.

While the new product will keep your camping supplies nice and cool, Fenik’s mission is to provide an inexpensive food-preservation solution for people in developing countries who lack access to electricity and refrigeration. We caught up with co-founder Spencer Taylor to hear Fenik’s latest news.

What’s your founding date?

September 2013.

How big is your team?

Five people.

What problem are you solving?

Last-mile food insecurity in arid developing nations.

What’s been the biggest surprise about running your business?

How few true-impact investors actually exist. They are often talked about, but you rarely meet one.

What was the big idea that got you started?

In an MIT class called Development Ventures, on the first day the professor said, “I want you to come up with a good or service that will change the lives of one billion people.”

Whom are you competing with?

Primitive evaporative coolers, such as the Zeer Pot, or draping wet cloth over food to help to preserve it.

The coolest food system innovation I’ve heard of is…

the sheer amount of innovation going on in the food space these days.

The scariest thing about today’s food system is…

the amount of waste that is endemic throughout the cold chain in both developed and developing markets.

What’s your latest big news?

We’re taking delivery of our first production units of the Yuma in January 2019.

Best advice you’ve received?

Hardware is hard.

What advice do you give to potential startup founders?

Start with a problem you have experienced, or one that you deeply understand through others. Assume nothing and validate your approach compulsively as you progress with your client base. Constant course corrections are not the product of inexperience; they are critical to success.

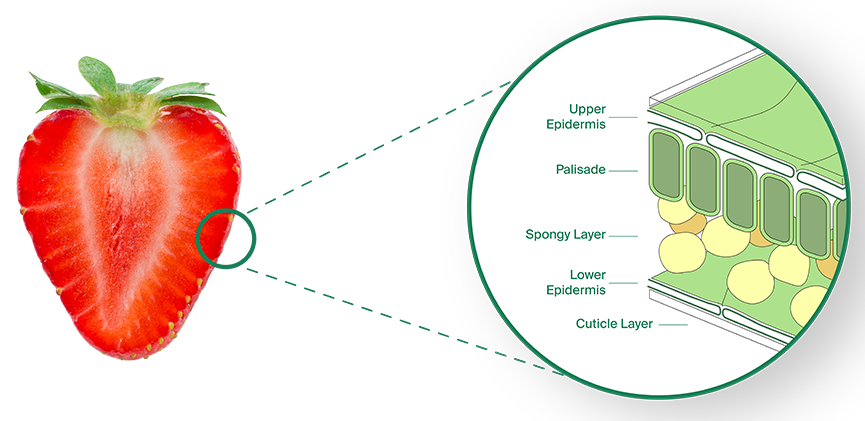

The Yuma No-Ice Cooler assembles easily and needs only water for evaporative cooling. The water is stored in the cooler’s walls and lowers the internal temperature 10-20 degrees — or more in drier environments.