Stories

Robyn’s Corner #4

Challenge Updates

Italian with Duolingo:

Still on track for daily practice, but my two kids and a friend are way ahead of me. Am going to experiment with a few YouTube Italian conversation sessions. Just experiment. Am going to Italy this month and still feel confident about mumbling Italian but not really taking on a conversation.

Drawing:

Completed a full month of daily drawing. I loved this challenge. It was always a highpoint of my day, even though sometimes I felt out of ideas for subjects and also rushed on some days when I barely had time for drawing anything. I did learn a lot: new materials such as liquid watercolors, watercolor brush pens, white ink pens, and felt pens. For March, I want to continue with a daily drawing but because of SXSW and travel, I imagine many will be quick pencil sketches done on the run. Aim to get at least 75 percent of my goal this month. That would be 3 not 4 weeks of drawings, I guess.

The Library Book, by Susan Orlean. Being from Los Angeles, this book piqued my interest. Downtown LA appears out of the hazy Southern California sky as a jumble of high-rise concrete buildings. Nested on Hope Street, is the LA County Library, built in 1926 and burnt down by an arsonist in 1986. The building survived but millions of documents were incinerated. Orlean tells the story of the event while shining a light on libraries in general at a time when we download our books. By the time she has wandered through the library and its conflagration, you might find out who the arson was..maybe.

Having met Dan Ariely this past fall at Poptech, I wanted to learn more about his ideas around consumer behavior. This past week, I read Predictably Irrational, and enjoyed his easy to read prose along with his relatable ideas about why we do things that appear irrational. Great insights about why we eat unhealthy food, and pay too much for things we don’t need. This was an unexpected complementary read to the book I read last month about Adam Smith. Ariely puts Smith in a contemporary context, creating some new ways of looking at supply and demand.

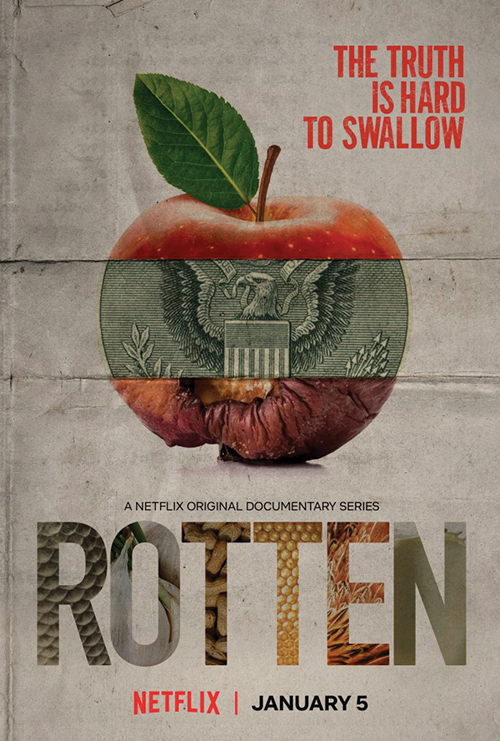

Food Routes……My book is out! You can buy it here: …….Would worship you if you bought one and then wrote a stunningly positive review on Amazon. Am grateful to my publicist at the MIT Press; he is doing a great job getting the book out there. Last week, The Wall Street Journal published my article about chicken tracking (J) and then NPR put me on Morning Edition. Then PBS filmed a short segment on pizza as a homage to Pi Day, March 14th. Am writing several pieces for media outlets and hope they run them. It’s all fun, if not intimidating. Enjoyed signing books at SXSW.

This is the month that Austin attracts creatives and technologists from all over the world. Even without an official badge, you can learn about ideas from unexpected places. Will head into the festival this week, starting with our Food+City Challenge, then my panel on The Future of Eating. Psychology professor, Art Markman, Futurist, Max Elder, and Smart City Evangelist Henry Gordon-Smith were rock stars on the stage.

Caught the Oscars (my allegiance to my home town runs deep). I found The Favourite a little strange but the acting and costumes were superb. This article by Amy Froide in The Conversation, a cool and smart website for news, shares her historical perspective on women at the time of Queen Anne. The whole idea that women were shrewd investors then was a surprise to me. I suggest that reading her book about women investors in the 18th century would be full of such insights.

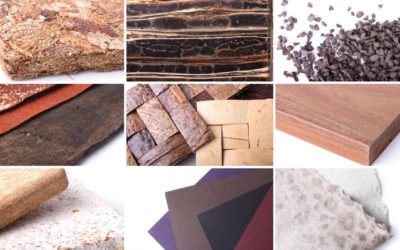

Now Available: Food Routes

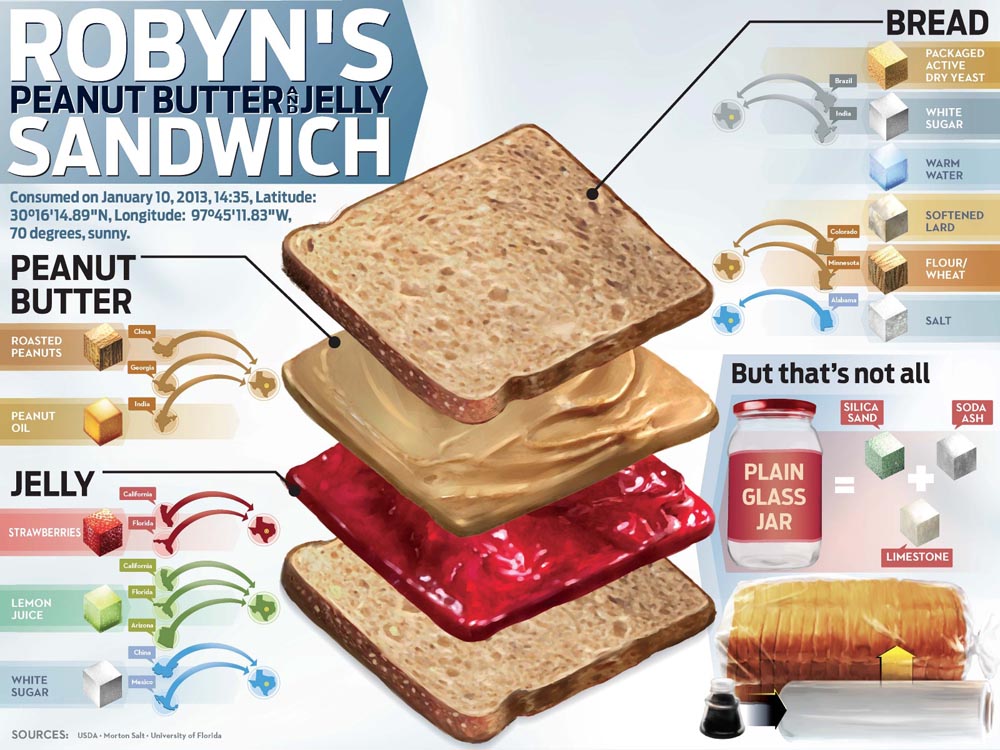

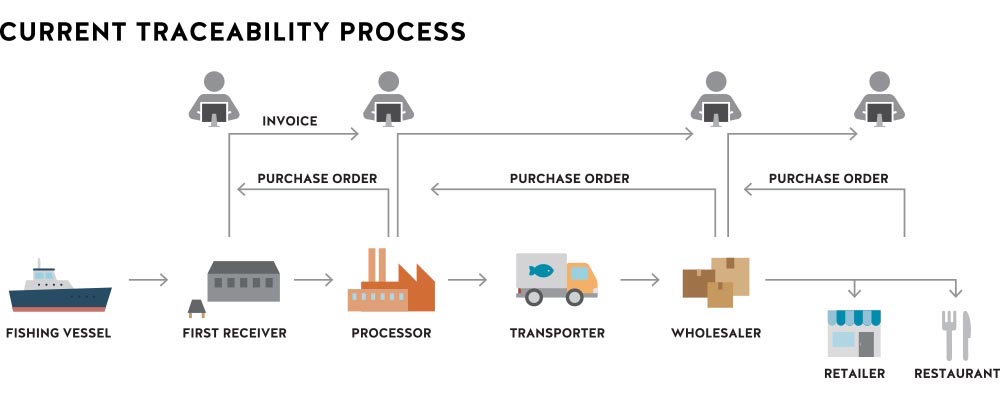

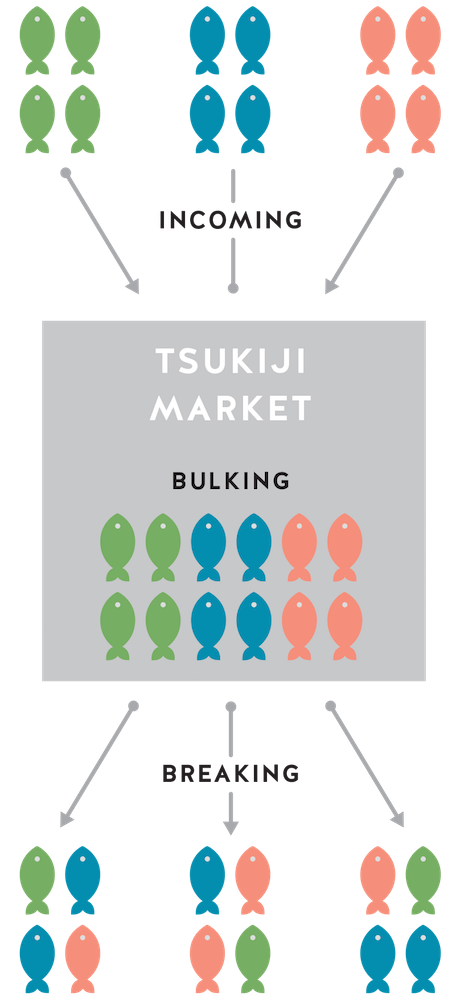

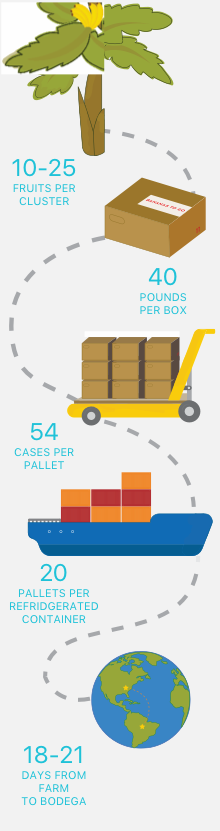

Even if we think we know a lot about good and healthy food―even if we buy organic, believe in slow food, and read Eater―we probably don’t know much about how food gets to the table. What happens between the farm and the kitchen? Why are all avocados from Mexico? Why does a restaurant in Maine order lamb from New Zealand?

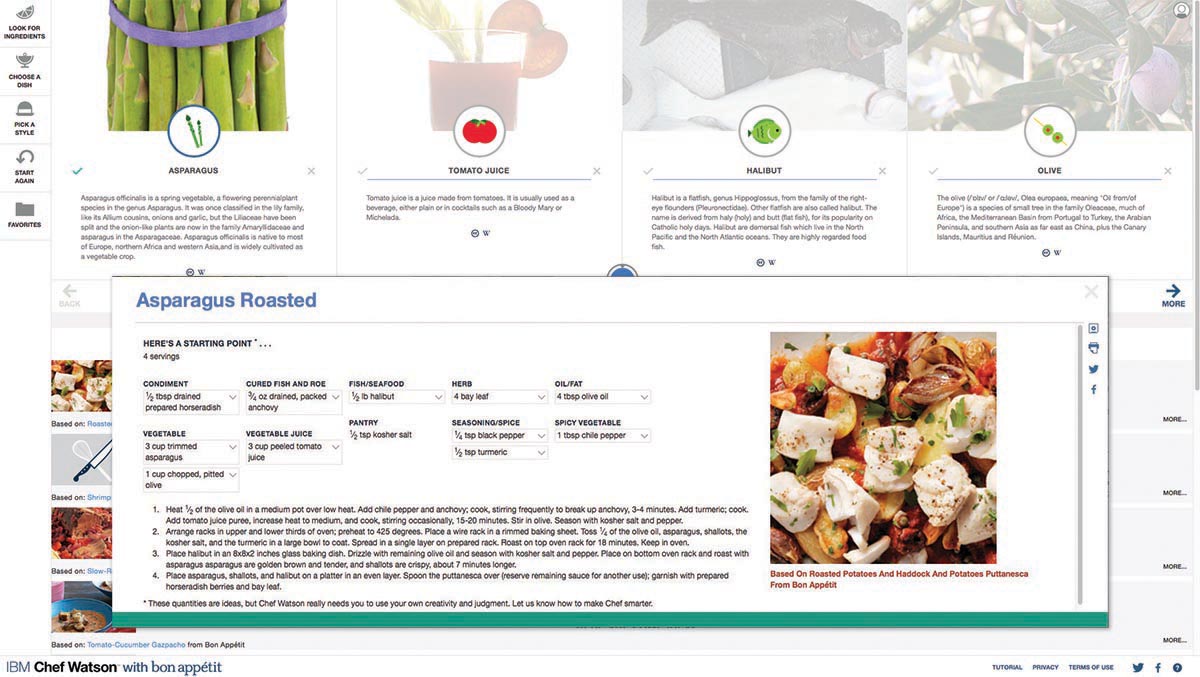

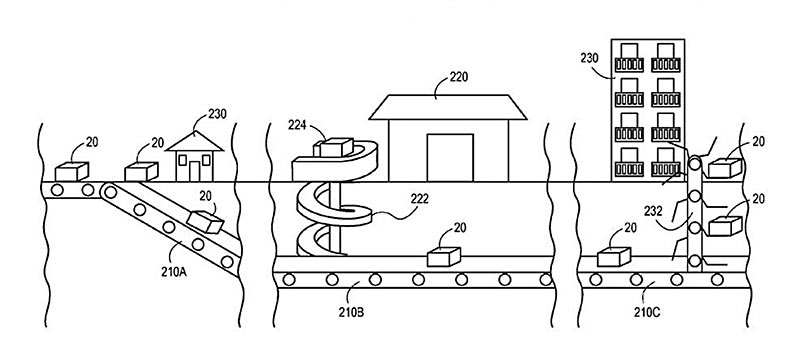

In Food Routes, Robyn Metcalfe explores an often-overlooked aspect of the global food system: how food moves from producer to consumer. She finds that the food supply chain is adapting to our increasingly complex demands for both personalization and convenience―but, she says, it won’t be an easy ride.

Networked, digital tools will improve the food system but will also challenge our relationship to food in anxiety-provoking ways. It might not be easy to transfer our affections from verdant fields of organic tomatoes to high-rise greenhouses tended by robots. And yet, argues Metcalfe―a cautious technology optimist―technological advances offer opportunities for innovations that can get better food to more people in an increasingly urbanized world.

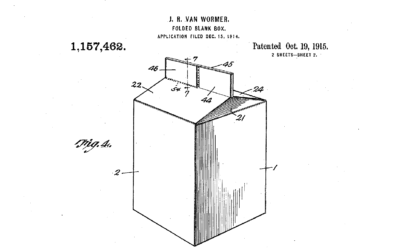

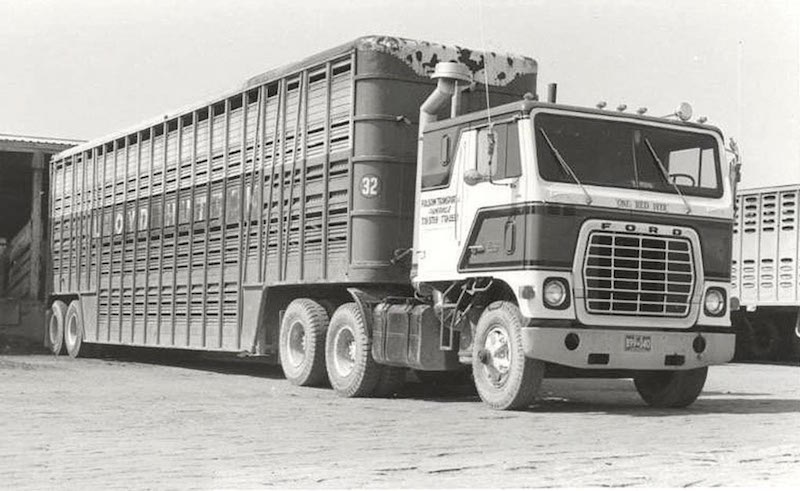

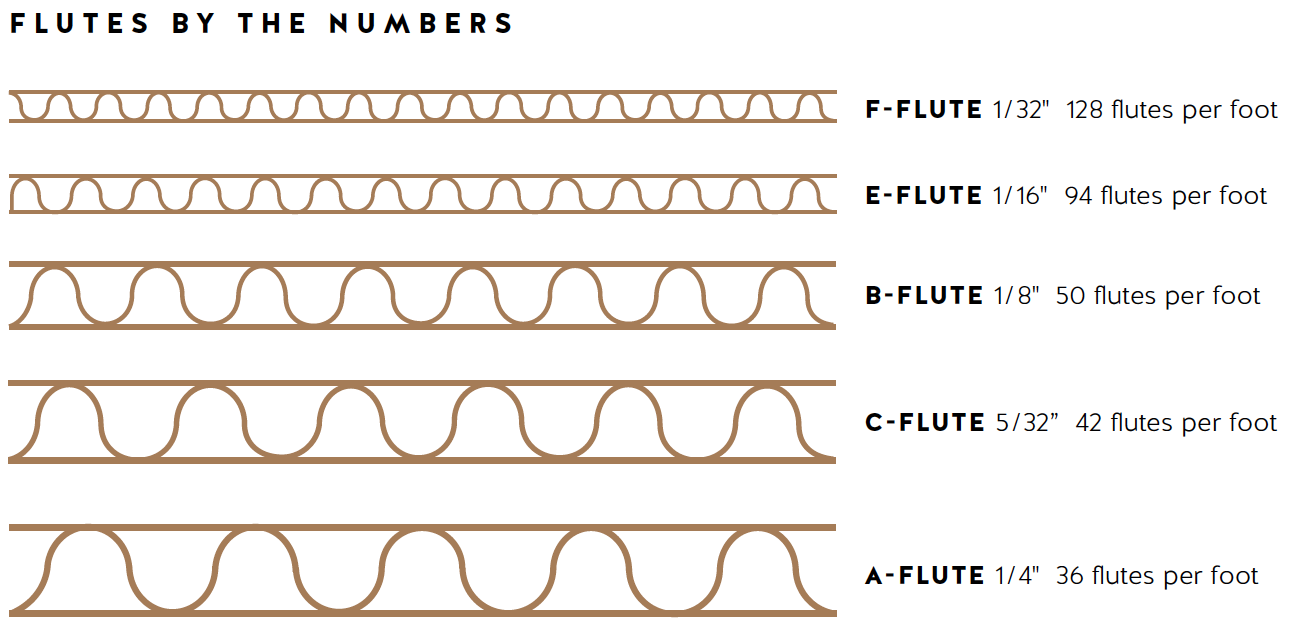

Metcalfe follows a slice of New York pizza and a club sandwich through the food supply chain; considers local foods, global foods, and food deserts; investigates the processing, packaging, and storage of food; explores the transportation networks that connect farm to plate; and explains how food can be tracked using sensors and the Internet of Things. Future food may be engineered, networked, and nearly independent of crops grown in fields. New technologies can make the food system more efficient―but at what cost to our traditionally close relationship with food?

Food Routes is now available for purchase on Amazon.

Robyn’s Corner #3

Challenge Updates:

February is half gone and I’ve done one sketch a day and kept on Duolingo for Italian. So far, holding steady.

A Most Unlikely Twitter Account:

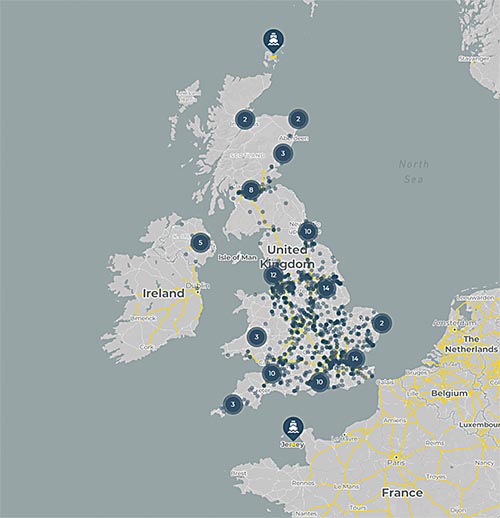

The Museum of English Rural Living Tweeted what might seem a shocking image on Valentine’s Day. The Tweet is just one of many delivered by a crack social media team that manages to engage its over 100K followers every day. They pull it off with a sense of humor, smartness, and loyalty to the museum’s mission. They dig up images from the archives, find a way to inform while amuse, and sure enough, their followers come back with sometimes long and surprising retorts and comments. There’s much to learn here and it may take more than a month of Tweets before their secret sauce becomes apparent.

WIP (Works in Progress)

- Podcast progress: Just before Christmas, I took the plunge to start a Podcast. Yes, everyone seems to have the same idea, so no credit for originality here. It’s just that blogs have become such a slog for so many. How to share a story without contributing to the noise in the ether? I found three willing subjects for the first three episodes: an expert on GMO salmon, food logistics expert and an professor of international food businesses. I’ve got the recordings, found someone to help with editing and launching, and am now considering what I should call the podcast. For the moment, I’m taking a step back, considering the audience and how the podcast could be interesting to more than one or two listeners. Stay tuned.

- Geocaching: The one that got away: Over the holidays, I fell for geocaching, the odd sport of finding hidden objects using only a few hints and some compass coordinates. The geocaching crowd consists of yet another nerd cult. And now I know why. Finding these small capsules, hidden boxes, and clues, brings out an obsession with detail and stirs it in with the surreal feeling of living in an alternate universe, filled with Mugglers and people wandering in parking lots and gullies. While on holiday in San Diego our family nailed at least five caches in an hour, actually post mid-night on New Year’s Eve. Back in Austin, I found three in and around the parking lot near our home. When you fail to locate a cache, you must log a Did Not Find note on your profile within the Geocaching.com app. Although I am sure no one cares, it feels like a low blow. I’ve returned to the location where the cache is supposed to be now at varying times of the day, wandering around, looking up, down, up into trees, in drain covers, all over the grass dividers ….. while nearby shoppers regard me with mild suspicion and certain curiosity. Am not sure how to recover from this loss, the inability to ever find another cache other than in the post New Year’s Eve haze. Have begun to search for easy caches, those rated on the app as easy finds and see if I can redeem just a modicum of caching confidence.

The Transalpine Run August 31 through Sept 9, 2019

8 days, four countries 275 KM, 170.87 miles) and 16,416 M of positive vertical ascent (about 10 miles).

This is the race I’m doing this year. It’s epic and it will be the second time for me; I ran this 10 years ago. My running partner and I aim to complete this together and as artists, we are a team names “Sketchy Sisters.”

| SKETCHY SISTERS | Metcalfe Robyn w | Austin | Bazany-Taylor Alexandra w | Maidenhead | SENIOR MASTER WOMEN |

We have about 6 months left of training. As of now, we are doing our own training thing, building and maintaining our foundation with lots of cross training. For me this means every week I get in three days of running (a total of 20 miles, broken into three runs of one long, one hills, and one speed. Also 3 days of bike trainer workouts using Zwift. Two days of strength training and one day of boxing. This means double workouts on some days. During the next few months, Sandra and I will work together to do more hills, work on equipment, and work out the logistics for 8 days of runs. Mentally, we are already in the game. We’ll work on what we think we can control and leave the rest to surprises and adventure. You can follow both Sandra and I on Strava, if you are curious about our daily workouts. Other friends and family are joining the run this year, all 8 of us. Very exciting.

Sandra and I had a tough time during the first day of the race when we did this before, so Sandra and I will plan to meet at the race start in June to train over that first day’s route, just to get over it and not have it buffalo us again.

This week, I worked out a way to keep track of my hill repeats. There were 10, as you can see here.

Book Reading:

Read Ryan Holiday’s Conspiracy: Peter Thiel, Hulk Hogan, Gawker, and the Atomy of Intrigue. This is a riveting read as Holiday takes you through the conspiracy of Thiel’s team and Hulk Hogan to attack Gawker. While the lawsuits did achieve their intended goal of bankrupting Gawker, Holiday wonders if conspiracies have lost their role in today’s culture of self interest and a fragmentation of resolve.

In a strange way, another book I’m reading, Bene Brown’s Daring Greatly explores vulnerability and shame in a way that resonates with many of the characters in Holiday’s book. Finding connections between books is always a surprise.

Am also working my way through a biography of Adam Smith called Adam Smith: An Enlightened Life by Nicholas Phillipson. Am only through the first third of the book and it’s a bit slow going as the author lays out Smith’s background and the ways the Scottish Enlightenment informed the basis of his economic philosophy for The Wealth of Nations.

Doodle of the Week: Teacups 8 Ways

Pen, Watercolor

Robyn’s Corner #2

January Challenges:

- Restart Italian Lessons on Duolingo. So far 1458 points, compared to my son’s 5780 points for Portuguese and daughter’s 1201 points for French. But, hey, my son is highly motivated since he married a Brazilian woman and my daughter has only just started. Yeah, we’re competitive.

- Read a book every two weeks. So far, so good, with three read in January (see notes below). One was really short, so is that cheating?

- Get back to sketching. Nope, total fail. Watch for my new February Challenge.

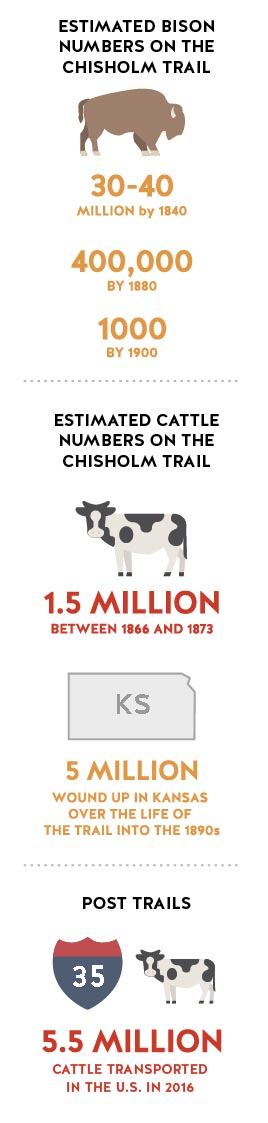

Lost Opportunities?

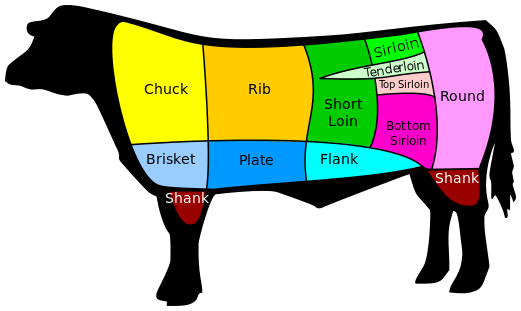

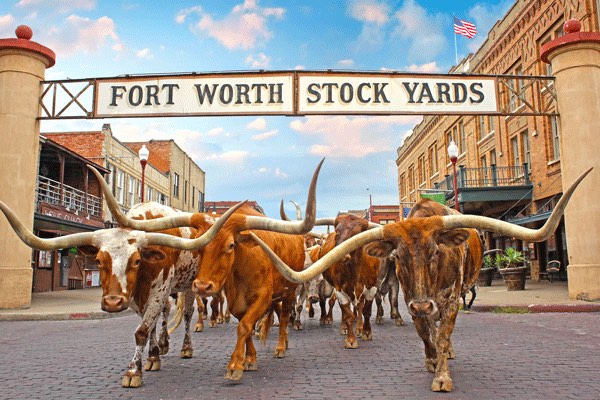

Did you know that The University of Texas’ mascot, BEVO, is an endangered livestock breed and that there are only 1,200 purebred Texas Longhorn cattle left in the US? This breed is disappearing because most ranchers don’t want to deal with those enormous horns and instead cross them with other less-horny breeds so they can benefit from the Longhorn’s unique genetics while avoiding those hook’ems. I bring this up because the University has an opportunity to make the breed its poster-child for the conservation of agricultural biodiversity. Why not use $1 from each athletic event at UT to fund a conservation program at The Livestock Conservancy? And to engage ag students to find a market need for these creatures so that farmers will add a few of these impressive cattle to their herds? Just wondering. Seems so obvious a win for ag and a creative way to support diversity.

Anniversaries: Memories of Boston’s Great Molasses Flood of 1919

In case you missed this, on January 15th, one hundred years ago, over two million gallons of molasses burst from storage tanks in Boston’s North End. A combination of warming temperatures, ethanol, cold syrup, and decaying storage tanks all contributed to the wave of sticky molasses that rolled through the area, killing 21 people and injuring over 100 people. I noticed this when researching the history of food supply chains. Could this happen again today?

Unexpected and Surprising

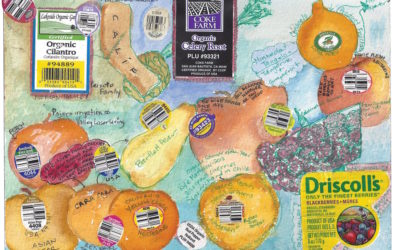

While attending the Antigua Forum in Antigua, Guatemala (of all places) I learned about the history of Haas avocados, our current toast obsession. In the 1920s, Wilson Popenoe of The United Fruit Company brought the Antiguan variety to Southern California where it eventually became the Haas variety. A plaque in Antigua presented in 1946 by the California Avocado Society celebrates the connection with Antigua; in the 1950s, I remember three avocado trees growing in our front yard. I’d pile the ripe ones in my red wagon and sell them door-to-door on the street where we lived. An early startup venture. Wonder if they were the new Haas variety? (See my doodle below)

Books Read in January

- In January, I read three books, each entirely different. Edward Dolnick’s Clockwork Universe covers enlightened, scientific thought from Aristotle to Sir Isaac Newton. He explains how scientists began to view the world as a machine, decipherable through an enlarged understanding of mathematics. He moves from Copernicus to Galileo, Kepler, Newton, and finally to Leibniz, showing how each built their theories upon others, some arguing, disputing, and sometimes stealing the ideas of their peers. Looking forward to re-reading the last chapter of Newton’s The Principia, written in 1729, where Newton’s spiritual views come to the surface. “This most elegant system of the sun, planets, and comets,” he says, “could not have arisen without the design and dominion of an intelligent and powerful being.” Another example of how art, science, and spirituality comingle.

- J. Jacobs book, Thanks a Thousand (A Gratitude Journey) is just that. A journey from a field of coffee beans to his morning Joe. He seeks out 1,000 people who brought him his cup of coffee and personally thanks each of them. Not only does it reveal just how many people perform the tasks required to deliver a simple food item, but mostly how important it is to practice gratitude. Not naturally an optimistic, grateful sort, he is honest about how challenging it is for us to stop to thank those who perform simple tasks. Inspiring and a quick read.

- H is for Hawk, by Helen MacDonald is not a quick read. I picked up the book after taking a lesson in falconry over the holidays and remembered that the book also related to the death of the author’s father. My dad passed away in September, so the two touch points pulled me into her story. Don’t even think about trying to skim those pages for you’d miss her exquisite prose, words that pop, stop, and pleasantly ramble. The passing of her father creates a compulsion to return to her hobby of falconry. Her story exposes her pain and the process of finding her place in a new landscape. So much to learn here about falcons, especially Mable, her goshawk. In the end she her new landscape embraces her as she rediscovers love and a balance between humans and the natural world. There’s a quick trip to Maine near the end that reveals Maine’s falconry culture, a far cry from MacDonald’s Cambridge fens.

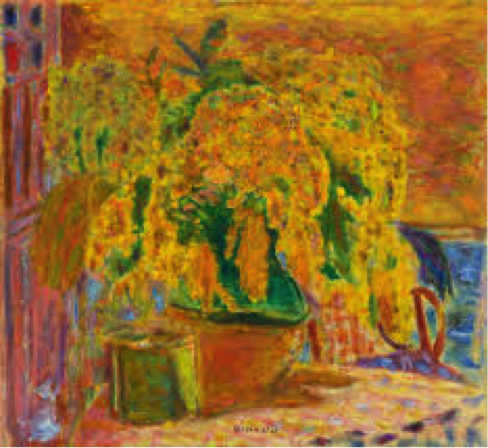

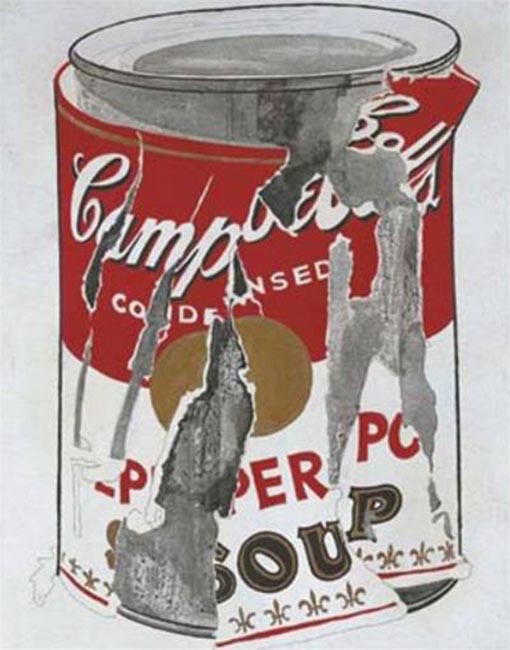

Manic Color: Pierre Bonnard exhibit at London’s Tate Modern

One of my favorite museums is the Tate Modern in London. This month it opened an exhibit of paintings by Pierre Bonnard from around 1912. His paintings are full of vibrant color, everyday domestic scenes, transparent yet luminous. Rich layerings of texture and color.

What better canvas for Bonnard’s colors than my own hair, noted above over the past year or so.

Sundance Film Festival, just a taste

For our 39th wedding anniversary, my husband and I attended the Sundance Film Festival and saw (among other films) the premiere of The Innovator, a film about Elizabeth Holmes and her company Theranos. Most of you will be familiar with the rapid rise and calamitous downfall of the company. Ms Holmes and her former partner (the COO) are currently awaiting trial for wire fraud … among several other counts of fraud. The company has dissolved. The story is dramatic; woman drops out of Stanford, creates a company built upon the promise of making blood tests accessible and affordable to the public. The problem appears to be a combination of a bold vision, miscalculations of the complexity of the problem, and a total lack of transparency. While the film seems to disparage Silicon Valley startups as being arrogant and irresponsible, perhaps a lesson for us here today is that, like technology for blood testing, technology in our food system can have direct life and death consequences. Food poisoning for example. Perhaps, the lesson one could draw from Theranos is that when it comes to startups with ideas that involve our personal health, we need to be even more diligent about the consequences, on multiple levels. Human privacy, physical integrity, health. While the payoff can be huge, transparency, personal control of our health, less waste, the downsides are also huge….some of Theranos users received test results that falsely indicated they had cancer. Innovation in our food system will deliver positive results, but requires extra due diligence not apparent in the Theranos story.

Other films of note that we saw: (star-ratings, totally my own)

Monos: (3 out of 5 stars) Lord of the Flies meets Apocalypse Now

Share: (5 out of 5 stars) Moving story about a young girl who survives the fallout after images from a night she can’t remember appear on social media.

Sea of Shadows: (4 out of 5 stars) Panoramic, action-filled account of the Mexican Mafia, Chinese traders, and the loss of sea life in the Sea of Cortez. The main character is an endangered whale, the vaquita, the world’s smallest whale. Only 10-15 remain, threatened by sea nets used to catch totoaba; the Chinese falsely claim the totoaba bladders are a remedy for various diseases. Intense film, a grim view of how multiple levels of corruption cooperate.

Robyn’s Corner

1.)Food+City has done its share of conferences and events, so why wouldn’t you do one for fun, real fun. Our family (Metcalfe’s) is crazy about running, food, maps, travel, and prime numbers, it seems. But it is always up for dry, sarcastic humor. Even dark, sometimes. This Christmas, my family held its sporadic Metcon conference. Sporadic because it last took place in 2015. We copy normal conference formats, including pre-registration, registration, an icebreaker, presentations, badges, and breakout sessions. A full house is all five of us. If you want a full debrief of the conference this year, email me at info@foodandcity.org.

2.)Am in the process of launching a podcast, something I’ve been curious about for years. In December I recorded three podcasts and am now working on packaging them for a soft launch to come. The first person I interviewed was Mark Walton. The podcast aims to explore what’s happens when technology affects everything we eat. Thanks to the enthusiasm and support from Laura Lorek who showed me the ropes.

3.)At Food+City, we publish a magazine as a way to introduce our readers to the art and science of feeding cities. After 4 issues, we discovered that our beautiful and carefully researched and written magazine wasn’t getting read. Well, it was, by our dozen or so friends and family. So we’re headed back to the garage to see how best to share our stories. Instagram? Youtube?

4.)Tuesday, my book editor and I headed out to visit Steven and Carey Kraemer, owner of Buena Tierra Farm. We are prototyping a new book project that would include photos and stories about the people who are invisible workers within our industrial food system. While the Kraemers are not of industrial size, they were gracious enough to allow us to test our interview style and photo/recording technology. As it turned out, an unexpected story did emerge from our visit, which you can read.

5.)Am always interested in anyone working on sensors for our personal biometrics. Check out UT’s Division of Textiles and Apparel’s event hosting Dr. Juan Hinestroza from Cornell University, called Fashionable Nanotechnology. Wouldn’t you hope he will show how fibers can be smart?

6.)My forthcoming book, Food Routes: Growing Bananas in Iceland and Other Tales from the Logistics of Eating, will be published by the MIT Press in March. It will be available at SXSW in Austin this year, on Amazon, and in a bunch of independent bookstores. After three years of writing, which included writing two versions of the book, I am almost ready to find a new project that enables me to learn something new. More on that in a later newsletter.

7.)This past weekend, I attended the Antigua Forum, an annual meeting of free-market thinkers who spend the weekend solving problems using a process similar to a hackathon, but better. The ten challenges included finding a way to generate new sources of energy in Lebanon, developing a grass roots project in Senegal to enable entrepreneurs to begin to own and operate their own businesses, developing an integrated health care system that enables individuals to control their own health data. The Forum has some good ground rules, such adding value, not engaging in a critique of ideas, and engaging in the small group format. The process was similar included the design thinking process but included some pretty impressive methods for following the projects after the conference. Congrats to the facilitators; they were impressive.

8.)Books, movies and stuff I’m listening to:

a. I’m reading this month. Just completed The Clockwork Universe, by Edward Dolnick. While you might find the long sections on how to calculate the speed of a falling rock, the book gives you an overview of how we began to use the language of calculus and mathematics instead of relying on empiricism and observation. He begins with Aristotle, Euclid, and ends with Newton and Liebnitz. After seeing the Super Blood Moon last night and hearing the scientists explain the phenomena, it is clear that we’ve come a long way since Galileo looked at the moon.

b. Watched the Netflix movie, Bandersnatch, inspired by Black Mirror. After choosing all the alternative story lines, using a remote for our TV, we finally arrived at and ending that sort of made sense to us. Being in the story feels almost like losing the serendipity of discovering the story rather than shaping it. Almost too much control. If that’s possible….

c. During training runs and bike workouts, I’ve been enjoying Tim Ferris (Interview of Greg McKeown, the author of Essentialism. I read his book a couple of years ago and now he’s gotten even better describing how to say “no” to all those projects that distract you from what’s important. Freakonomics continues to inform, now about sports with its series “The Hidden Side of Sports.” Lots there to learn about mental discipline.

This week’s doodle: “The Tower” – Buena Tierra Farm

Startup Spotlight: FENIK

Originally known as Evaptainers, Fenik started out as a student project at MIT. The team’s goal was to develop a low-cost method for preserving fruits and vegetables in remote areas. Five years and many prototypes later, Fenik recently wrapped up a successful Kickstarter campaign and launched production of its Yuma No-Ice Cooler.

While the new product will keep your camping supplies nice and cool, Fenik’s mission is to provide an inexpensive food-preservation solution for people in developing countries who lack access to electricity and refrigeration. We caught up with co-founder Spencer Taylor to hear Fenik’s latest news.

What’s your founding date?

September 2013.

How big is your team?

Five people.

What problem are you solving?

Last-mile food insecurity in arid developing nations.

What’s been the biggest surprise about running your business?

How few true-impact investors actually exist. They are often talked about, but you rarely meet one.

What was the big idea that got you started?

In an MIT class called Development Ventures, on the first day the professor said, “I want you to come up with a good or service that will change the lives of one billion people.”

Whom are you competing with?

Primitive evaporative coolers, such as the Zeer Pot, or draping wet cloth over food to help to preserve it.

The coolest food system innovation I’ve heard of is…

the sheer amount of innovation going on in the food space these days.

The scariest thing about today’s food system is…

the amount of waste that is endemic throughout the cold chain in both developed and developing markets.

What’s your latest big news?

We’re taking delivery of our first production units of the Yuma in January 2019.

Best advice you’ve received?

Hardware is hard.

What advice do you give to potential startup founders?

Start with a problem you have experienced, or one that you deeply understand through others. Assume nothing and validate your approach compulsively as you progress with your client base. Constant course corrections are not the product of inexperience; they are critical to success.

The Yuma No-Ice Cooler assembles easily and needs only water for evaporative cooling. The water is stored in the cooler’s walls and lowers the internal temperature 10-20 degrees — or more in drier environments.

Startup Spotlight: UAV-IQ

Using military-developed technology, UAV-IQ combines high-tech field surveillance, environmental sensors and specialized software to help farmers keep a close eye on their crops. Pinpoint imagery allows farmers to focus on problem areas — locating issues such as water puddling or the beginning of a disease outbreak — and address them before they spread. Information sensed by the drone, including images that show detail down to individual leaves, can be transmitted to tablets or other tools used by farm staff anywhere in the field. We caught up with Andreas Neuman, co-founder and CEO of the Food+City Challenge Prize 2018 winner, to get its latest news.

What’s your founding date?

April 2016.

How big is your team?

Five people.

What problem are you solving?

Precision agriculture has proven to be highly effective for growers who practice it, but many growers perceive pricing or lack of training as barriers to adoption. Starting with drone-based remote sensing (which tells growers where their crops are healthy and where they’re stressed), UAV-IQ makes precision agriculture technology accessible and implementable within existing workflows to growers of any size and sophistication.

What’s been the biggest surprise about running your business?

That there are so many people genuinely interested in helping young companies get started.

What part of the food system are you in?

We focus on helping growers.

What was the big idea that got you started?

That one of the most fundamental problems for farmers — identifying where their crops are struggling and targeting their treatments precisely where they’re needed — was a solvable problem by using properly equipped to drones to rapidly scout fields.

Who are you competing with?

Inertia — sticking with an inefficient status quo — is our largest competitor. We also compete with satellites and other imagery providers.

The coolest food system innovation I’ve heard of is…

The use of hyperspectral sensors to identify specific disease, ripeness levels and other qualities while the crops are growing.

The scariest thing about today’s food system is…

Lack of diversity.

What’s your latest big news?

We are starting to provide a new service that utilizes drones to drop biological control agents (beneficial insects) to suppress pest populations in California.

What’s the best advice you’ve received?

If it’s not a “hell yes,” it’s a “no” when contemplating early employees and partners.

What advice do you give to potential startup founders?

Focus on building the best team before focusing on building the best product or service.

Startup Spotlight: Vinder

Founded in Port Townsend, Washington, by Sam Lillie, Vinder connects home veggie gardeners with folks who want to buy that fresh produce. The app brings together community members who are interested in ultra-local food and reducing food waste. It also boosts the local economy by opening up a revenue stream for green thumbs who connect with their neighbors to share their garden’s bounty. We recently reached out to the 2018 Food+City Challenge Prize contestant to find out how things are going at Vinder.

What’s your founding date?

January 21, 2018.

How big is your team?

Four full time.

What problem are you solving?

Food waste, cost and food insecurity.

What’s been the biggest surprise about running your business?

As much as I heard and read about it, the investor “run-around” has been my biggest surprise. Most professional investors I’ve had the privilege to speak with don’t give a solid “no.” They give advice and information, which is great because it helps hone the pitch and business plan/strategy. But it may not be the right type of advice that works for your company or be useful when approaching other investors. It ends up being a massive time/energy zap.

What part of the food system are you in?

Vinder is situated in the distribution of hyper-local produce — neighbor to neighbor. Yet, we do not own any delivery vehicles or own any inventory.

What was the big idea that got you started?

My community, Port Townsend, Washington, had a big problem accessing local organic produce for a reasonable price. Vinder was created not to be some massive, disruptive company, but to solve a problem in my community.

Whom are you competing with?

For convenience, we compete with HEB or Whole Foods. For freshness and locality, we compete with farmers’ markets. However, we see ourselves as a tool to help those small vendors reach more customers and increase sales direct-to-consumer.

The coolest food system innovation I’ve heard of is…

a company called Vinder that allows you to buy, sell or trade homegrown produce and neighbor-made goods directly from your neighbors. It’s free to sign up and free to sell or trade.

The scariest thing about today’s food system is…

we have normalized an absence of connection to our food system. We have no idea what is actually going into the soil in which our food is being grown (or what chemicals are being sprayed on them), who is growing it or where exactly it is being grown.

What’s your latest big news?

We are now a user-owned and -operated company. After successfully closing an Equity Crowdfunding round of more than $85,000 via WeFunder and receiving matching angel investments, Vinder issued preferred shares to users who are taking a stand against our current food system and are opting to create the neighbor-made food system of the future. Vinder is also now available for iOS and Android.

Best advice you’ve received?

In the words of entrepreneur and venture capitalist Paul Graham, “Focus on getting 100 people to love you rather than 1,000 people to kind of like you.”

What advice do you give to potential startup founders?

You don’t need a lot of money to start a company. First, come up with the lowest-budget minimum viable product and validate that the market needs your solution. Then build out manually, followed by tech. Let tech be a solution to make a process more efficient rather than the primary focus.

Startup Spotlight: Grit Grocery

Grit Grocery has put a gourmet grocery into a food truck. Working directly with farmers and other local producers, Grit Grocery launched a fleet of grocery trucks to bring fresh ingredients and meal-kit bundles into urban areas — starting in Houston — underserved by traditional grocery options. We visited with cofounders Michael Powell and Dustin Windham to find out how they’re doing after competing in the Food+City Challenge Prize in 2018.

What’s your founding date?

Founded in 2015, pilot in 2016-2017, full-scale launch in April 2018.

How big is your team?

Five co-founders, plus a team of seven who drive trucks, sell food, work in the kitchen and organize the warehouse.

What problem are you solving?

Grit Grocery trucks bring fresh local food products to urban locations that don’t have food retailers or that have stores that carry mainly processed nonperishable food. We’ve designed a shopping experience that provides ideas and inspirations for healthy, easy, fresh, local-food meal solutions, tonight.

What’s been the biggest surprise about running your business?

A lot of local brands are producing and growing great food, but they don’t have access to customers through a retail outlet. We get a lot of these groups asking to get their products on the truck. We also hear from apartment complexes and developers requesting that Grit be at their residences. We already have a long waiting list of sites.

What part of the food system are you in?

Grit Grocery is a retail destination. We source directly from local farmers and ranchers as much as possible. As a retailer, we are at the front line of customer interaction.

What was the big idea that got you started?

Why is it so difficult to put together all of our meals over the course of the week with fresh, local, healthy food? There’s something wrong with food retail — and with the traditional grocery store model, in particular — that makes it hard for so many people to eat healthy, find local foods and put together meals. While we’ve seen a lot of innovation in how food is grown and produced, retail innovation has been lacking. New online options are promising but lack the flexibility to be a good fit for today’s urban life. This is where Grit Grocery started.

Whom are you competing with?

Traditional grocery stores and other big-box stores are obviously the main source of food retail. Organic and specialty grocers offer food more in line with what Grit offers, but they mainly carry nonlocal food and a lot of processed food. Farmer’s markets are not competitors, but they do overlap with Grit’s offerings — though their shopping experiences are not strategically designed for customers. Online grocers and meal-kit providers are similarly flexible when it comes to delivering food retail access, but they also come up short in responding to a customer’s daily food issues and needs.

The coolest food system innovation I’ve heard of is…

Coolbot. Build a poor man’s walk-in cooler.

The scariest thing about today’s food system is…

Nowadays, food is everywhere you look, from the airport to the hardware store, schools to the office. But most of it seems to be processed junk. Society is busier than ever and we have created more on-the-go occasions to eat food than can possibly be healthy, or that can accommodate real food solutions. The processed food industry likes that and profits enormously.

What’s your latest big news?

We released a Chatbot in October 2018 that allows people to use their smartphone to order a meal for pickup at the truck. They can also use the Chatbot to find the Grit Grocery truck and order a Grit-Together, a unique dinner party event for small groups.

Best advice you’ve received?

Be resilient. That’s what grit is all about. Keep trying new things, putting ideas into action and watching to see what works and what needs further improvement.

What advice do you give to potential startup founders?

Good strategy and technology are not enough. People and their food habits are kind of weird and hard to predict. You need to test and get in front of people, see how they really engage with your food or product in their daily lives.

Grocery Stores: The IoT of Food

Tired of comparisons to the much flashier internet, supermarkets are working hard to ditch their unsexy descriptor: big-box stores. These days you’ll find a Murray’s Cheese outpost in Kroger, a kombucha bar at Whole Foods and poke bowl counter at Albertsons. All these flashy foodie options are good distractions from what’s happening under the hood, which is that grocery stores — the physical four walls — are going digital.

Ready or not, consumer packaged goods (CPGs) — those pre-wrapped items found in so many center aisles — are nudging grocery stores into the future. And so is Amazon. The online retail giant’s entrance into brick-and-mortar supermarkets forced every retailer to innovate or die.

It’s been decades since the internet changed the way we shop, so why are American retailers slow to get on board? The founders of Trax, a retail technology firm based in Singapore, might point to our love for the status quo. The U.S. Census Bureau’s figures (from second-quarter 2018) bear that out, indicating that e-commerce sales account for 9 percent of total sales. That means 91 percent of sales still occur in stores. Maybe U.S. retailers aren’t scared yet?

In contrast, the true retail visionaries are found in Australia, Brazil and China. Yair Adato, Trax’s chief technology officer, says China is five years ahead of the U.S.

“In China, you can go to a store, scan what you want to buy, put it in your cart and they’ll deliver it to your home in 30 minutes,” Adato says.

Soda giants were early pioneers in creating speedy distribution channels. Yet despite raking in billions of dollars in sales, they couldn’t point to exactly how, when or why. Brands were guessing what was on the shelf, how much was left, what was selling at what times of day and even what their competitors had on the shelf. Short of physically walking in to every single store in the world and snapping a photo of the soda aisle, they had no idea what was happening.

In some countries, brand managers might have trusted their employees when they said they went to a store and reported that everything “looked good.” But in China or Brazil, managers wanted visual proof. “It’s a culture thing,” said Adato. “I want to know that I paid the right bonus to my employee.” In Australia, instead of proof, they wanted to improve processes using data analytics.

But it was a little bit like the chicken and the egg. Brands wanted to harness data to make better business decisions, and stores wanted to evolve. They saw that online shopping was more engaging for customers than a trip to the store, but it was an expensive undertaking with no clear financial incentive for either party. While a brand like Coke might want to push retailers for improved ways of tracking its sales, the reality is that it has only a few thousand SKUs (aka, inventory items). Target, on the other hand, has hundreds of thousands. But before it could become cost-effective for retailers to adopt new tracking tools, the technology — sensors, beacons, cameras — needed to advance.

In 2010, Trax began offering its image-recognition software, which incorporated physical images (taken by humans) and store data (including store layout and register sales), then stitched them into one actionable gold mine. For the first time, sales teams could have detailed product and category information including out-of-shelf, share-of-shelf, planogram, pricing and promotional compliance delivered to their mobile phones in real time. This was something managers could trust.

“In a grocery store there is so much dynamic movement,” says David Gottlieb, vice president of retail at Trax. “Something like 40 percent of products will change — a new item, or line extensions and new packaging.” Gottlieb deeply understands the in-store problem.

“Manufacturers are using us, even without feet on the street [robust sales teams] to collect information to get true metrics as to what degree their customers are making perfect stores, and that incentivizes the sales team to do a better job,” explains Gottlieb. He joined Trax in 2018 when the company purchased his startup, Quri, which used a crowdsourcing model to leverage large groups of people to perform paid “microtasks,” like taking images of store shelves.

With the acquisition, Trax now has half a million shoppers active in 6,000 U.S. cities with access to 150,000 stores. Despite this, the company is moving beyond human photographers and is beginning to install battery-operated internet-connected cameras underneath the shelves. The cameras take photos every minute of the day.

“It creates opportunity for use cases — like intra-day replacement,” CTO Adato says. “Our customers are looking at how long things last. That’s an indicator of lost sales that wasn’t available.” CPG clients that use Trax report their out-of-stock rates reduced by 10 to 15 percent and category sales (e.g., soda, crackers or condiments) increased by 3 to 5 percent.

While Trax was homing in on the perfect store, Shelfbucks, an Austin-based technology startup, was grappling with another unknown: marketing. Brands were spending money on in-store product merchandising displays to promote their products, but they had little idea what worked or whether they even made it to the floor. Erik McMillan, the CEO of Shelfbucks, made a fairly compelling argument for his technology: “You spend a $100, and you’re wasting $50.”

Through a fortuitous meeting with two of the biggest display producers in the U.S. — West-Rock and Menasha Packaging Co. — McMillan gained access to an untapped business opportunity that helped brands answer their age-old question: Does my marketing have an ROI?

If it sounds like meta-marketing-speak, that’s because it is. You send a physical piece of signage into your supply chain and on the other end it arrives at a store. It’s supposed to be put up somewhere, on the end cap (those shelves at the end of each aisle often filled with promotional items) or the shelf, but maybe it never makes it out of the back room. With no analytics, you’re left hoping for the best. Given the amount of money spent on merchandise promotion whose effectiveness can’t be tracked — a waste factor of 50 percent, according to McMillan — in-store marketing isn’t much better than shooting in the dark.

In coordination with brands, Shelfbucks puts sensors on displays, and in coordination with retail customers, it places sensors throughout stores. The sensors track the movement of the signage — whether it’s in the back room or out on the floor. When there are problems, Shelfbucks gets an exception report, which is sent to the store manager as an alert in the store’s task management system.

“We are literally generating data about something (store managers have) never seen before,” McMillan says. In 2014, one of Shelfbucks first customers was CVS Pharmacy; today Shelfbucks is in CVS stores nationwide. Fresh food is his next target. “We are focused on the three national chains: Kroger, Albertsons and Ahold USA.”

How these changes benefit consumers is open for debate. Perhaps it’s as simple as knowing our favorite soda — Dr Pepper Vanilla Float, perhaps — will never be out of stock again. And while it may seem as if the CPGs of the world are driving change, McMillan reminds us otherwise.

“Brands can’t force retailers to do anything. Retailers have the power. That’s a really important point,” McMillan says. “The brands have the money, and the customer buys their product, but the retailer owns the shopper.”

For a deep dive into grocery store technology, read Joseph Turow’s book, “The Aisles Have Eyes.”

For a deep dive into grocery store technology, read Joseph Turow’s book, “The Aisles Have Eyes.”

Related Stories

Markets Go It Alone

The buzzword for today’s brick-and-mortar retailer is “frictionless.” It refers to a shopping experience where customers can come and go with ease. It means not waiting in lines and never having to take cash or a credit card out of your wallet. Sounds dreamy, right? It’s happening now, and here’s where to find it.

Zippin: San Francisco, CA

When Krishna Motukuri’s wife sent him to Trader Joe’s for a bottle of milk, he came back empty-handed. Why? The checkout lines were too long. When he dug into a study from MIT that found 37 billion hours were lost waiting in line every year, he was stunned. Wanting to help solve this problem, Motukuri took his computer science background and co-founded Zippin.

But while most of us think of the physical store as the end goal, Zippin only wants to be the powerful back end. This month, the startup launched a basic concept store in San Francisco to showcase its technology. To get through the slick entry gate, customers scan a QR code on their mobile phones. Once identified, customers can pick up a can of mango La Croix, a bag of sea salt Boomchickapop popcorn or perhaps a deli sandwich. Soon after they pass through the exit gate, an electronic receipt is sent to the Zippin app. And that’s it. Zippin’s AI-based software platform will allow retailers to deploy a “frictionless” shopping experience that wipes out time spent standing in line. According to Motukuri, operators of physical stores would need only minor upgrades — weight sensors on the shelves and overhead cameras — at a cost of about $25 per square foot. These enhancements, along with Zippin’s software (charged on a monthly subscription) will tell a retailer precisely what has been taken off the shelves.

Amazon Go: Seattle, WA

In January, Amazon opened its first cashier-free store on the ground floor of one of its many offices in downtown Seattle. Called Amazon Go, the store is a free-for-all of convenience foods, meal kits; even beer and wine. As reported by Recode, by being first on the scene, Amazon hopes to “carve out a loyal customer base outside of its website and inside a physical store where the vast majority of food and grocery shopping still occurs.”

Shoppers with the Amazon Go mobile app gain access to the store with a QR code, shop for snacks, take whatever they want and then they “Just Walk Out” — the name for Amazon’s technology. This includes overhead cameras, weight sensors and deep learning technology that detects what shoppers take off the shelves or if they change their mind and put something back. When customers leave the store, the “Just Walk Out” technology debits their Amazon account for the items and sends a receipt to the mobile app. In August 2018, Amazon opened a second location in Seattle. Expect subsequent stores to crop up in San Francisco, Los Angeles and Chicago, where Amazon has already signed leases for two locations including one in the famed Willis Tower.

The Moby Mart: Shanghai, China

While Amazon wants to help us eat more snacks, Wheelys, a Stockholm startup, is developing a market on wheels stocked with hip sneakers, fashionable magazines and yes, milk and cookies. In collaboration with Hefei University of Technology and tech firm Himalafy, the team created a roving, train-shaped convenience store on the university campus, 450 miles west of Shanghai, that can be located using an app. Self-driving, drone-equipped, powered by solar and always open, The Moby Mart is a tech nerd’s space-age fantasy come true.

Wheelys’ foray into automation began with modular-bike cafes. The easy-to-schlepp coffee carts could be moved around Stockholm for anyone not ready to commit to a lease. It was so popular that by 2016 Wheelys had sold 550 bikes. Looking beyond their Nordic country for their next innovation, the founders settled on China because of its large population and the country’s near-ubiquitous adoption of phone payments. While The Moby Mart is still running in beta, Wheelys is moving ahead with what co-founder Tomas Mazetti is calling “magic tech,” or hidden tech.

“At the moment, we believe that hidden technology is the next revolution, not just in retail but in many industries,” Mazetti says. “Imagine walking in through an open door, seeing a beautiful pair of sneakers, trying them on and then leaving the store with them, without ever having talked to anyone or seen any security.”

Farmhouse Market: New Prague, MN

Thankfully, not every automated market is so hands-off. In Minnesota, married couple Kendra and Paul Rasmusson opened Farmhouse Market in 2015. The Rasmusson’s wanted to open a store that offered delicious goods from local farmers, but they knew that staffing a store (and raising their three small children) would be a big challenge. Undaunted, the pair came up with some ingenious ways to run a mostly automated farm store that has some human touches.

First, there’s a membership base — $99 to join and then $20 annually. Members (now in the hundreds) can drop by 24-7 and receive a 5 percent discount on all purchases. Nonmembers can get in on the action at specific hours during the day when there is an actual person behind the counter. And it’s not all that high-tech: Members and farmers use a keycard entry system, and motion-activated lights and tablets enable self-checkout. (There’s a one-theft-and-you’re-banned-forever policy.) The store, only 650 square feet, is monitored with remote cameras, and inventory is tracked digitally. As with every one of these stores, humans are still quite important. Ms. Rasmusson prices items from home and texts orders to suppliers.

Related Stories

How They’re Watching Us

In the early days, retail stores tracked customers via turnstiles. After turnstiles, some stores turned to electronic beams, while others used light sources to count traffic in aisles. These methods were largely impersonal — they didn’t capture our faces, our phones in our pockets and they didn’t connect the dots: Suzy likes to shop on Mondays, has three kids and prefers to buy name brands. These days, our favorites stores have that information and a whole lot more. Here are ways we’re being tracked:

Wi-Fi

Wi-Fi

While you’re wandering the aisle, your phone is busy looking for a Wi-Fi signal. Retailers can use this ping to track us as we wander the aisles wondering what to eat for dinner. This can be a good thing, says Mike Lee, an expert in supermarket behavior. “If done right, these tracking technologies can provide a wealth of data that can inform merchandising and layout decisions aimed at creating a more efficient shopping experience,” he says. Using GPS and Wi-Fi tracking tied to shoppers’ mobile devices allows retailers to deliver targeted messaging, advertising and coupons in a more precise manner.

Bluetooth

Bluetooth

Similar to Wi-Fi, Bluetooth is a wireless technology that allows our movements to be tracked by the persistent ping from our phone to any Bluetooth beacon within range. Although a weaker signal than Wi-Fi, Bluetooth is a good backup when Wi-Fi is disabled. If both of these are disabled on our phones, our phones still give off a traceable signal. According to Joseph Turow, in his book, “The Aisles Have Eyes,” our phones’ own signals can establish location within 150 feet. As long as there are several access points, Wi-Fi is accurate to within a few meters and Bluetooth can locate you to within a few centimeters. This means eventually you’ll be reading the back of a box of cereal and simultaneously receiving an alert to get a dollar off that very box.

Apps on Our Mobile Phones

Apps on Our Mobile Phones

Most cell phone makers disguise our Bluetooth signals using randomized codes. But if you have an app downloaded then you’re fair game. Recently, Amazon connected its Prime membership to its Whole Foods stores, offering discounts on certain grocery store items. How did they want us to connect our accounts? Using the Whole Foods app on our phone. If your location services are turned on, you can bet the retailer is watching you.

Sensors & Beacons

Sensors & Beacons

Most cell phone makers disguise our Bluetooth signals using randomized codes. But if you have a store app downloaded onto your phone then you’re fair game. Recently, Amazon connected its Prime membership to its Whole Foods stores, offering discounts on certain grocery store items. How did they want us to connect our accounts? Using the Whole Foods app on our phone. If your location services are turned on, you can bet the retailer is watching you.

Hidden Cameras

Hidden Cameras

Trax, a Singapore-based retail technology firm, makes battery-operated, wireless cameras. Mounted underneath the shelves, these cameras take pictures that allow retailers to know what’s in stock and out of stock (using sensors). The body of the camera is the size of a deck of playing cards. The camera lens, only 1 by 1.5 cm., extends out from the battery pack via a narrow ribbon and fits onto the edge of the shelf. The software’s image recognition enables any photos with people to be deleted immediately to protect shoppers’ privacy. The cameras talk to each other and to local servers inside the markets so that Trax can accelerate image processing on site to deliver real-time metrics.

Trax, a Singapore-based retail technology firm, makes battery-operated, wireless cameras. Mounted underneath the shelves, these cameras take pictures that allow retailers to know what’s in stock and out of stock (using sensors). The body of the camera is the size of a deck of playing cards. The camera lens, only 1 by 1.5 cm., extends out from the battery pack via a narrow ribbon and fits onto the edge of the shelf. The software’s image recognition enables any photos with people to be deleted immediately to protect shoppers’ privacy. The cameras talk to each other and to local servers inside the markets so that Trax can accelerate image processing on site to deliver real-time metrics.

Related Stories

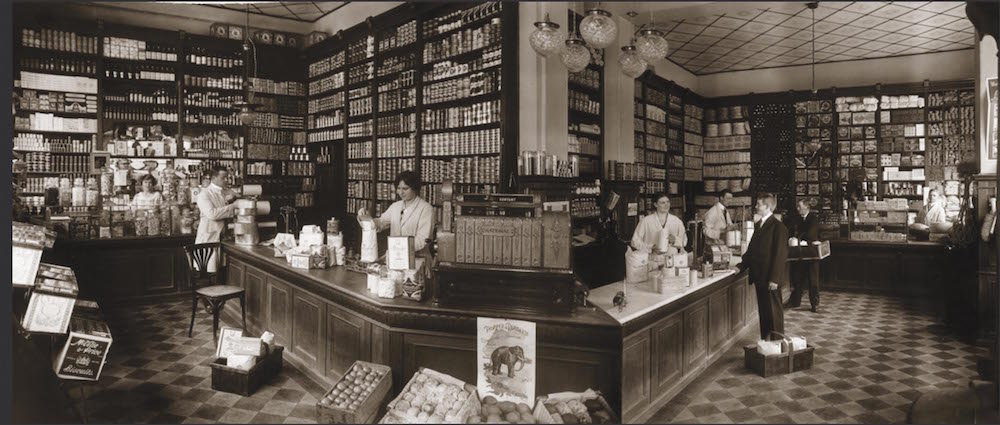

Side Dish Gallery: Mom & Pop Shops

As we conceived of this grocery-themed issue, our minds naturally went to the tech-laden big-box stores. But then we remembered how grocery began: the small, independent mom-and-pop shop. Here’s a selection of our followers’ favorite small groceries — some stores are thriving, while others are shuttered, perhaps depending on economic realities of the communities they serve.

Photos 1, 4, 5 and 7 by Robyn Metcalfe; photo 2 by Joan Phaup; photo 3 by Charlotte Herzele; photo 6 by Cole Leslie; photo 8 by Julie Savasky.

Trending: Grocery Stores, Meet Smart Kitchens

As i was leaving for the Smart Kitchen Summit in Seattle in October, my toaster broke. The ashen heating elements failed to flicker for one last slice of bread. In fact, all toasters — those kitchen staples since 1893 — may be on the way out.

Based on what I saw at the Summit, toasters — and practically all other kitchen appliances — are about to be unfamiliar in every way. Manufacturers promised that my appliances will recognize my face and voice to know my food preferences and biomedical data to produce the most perfect toast the world has ever tasted. And it won’t be a toaster, but a device that may toast, boil, sous-vide, fry or braise. Transforming ingredients into meals will be the goal of our new Smart Kitchen.

Imagine this: Your kitchen in 2030 will use voice activation to operate the handful of kitchen tools and appliances that remain after designers remove wires, Instapots, trash cans and microwaves. Your kitchen will be smaller and wireless, maybe even portable. Croatian startup Dizzconcept makes portable, pop-up kitchens that fit into any space. Perhaps our new homes will come without kitchens, and we’ll simply select these movable, modular, personal kitchens to drop into our new spaces.

Countertops will be charging surfaces for your devices. Screens will be voice activated (so you don’t have to touch a screen with fingers sticky from the syrup dispenser). These new surfaces will show what’s in your refrigerator and pantry, with data about the shelf life of all perishables. Your fridge will sense when you need to buy more milk — and will order it for delivery when your house knows you will be home. Garbi, another startup, is working on a trash can that recognizes what you discard, sorts it for recycling and reorders items.

Recipes will be personalized. No more single recipes from that book on the shelf, printed on paper, that may be good for someone but not you, with your recent calcium deficiencies and preference for mild flavors. Your kitchen will know what’s in your pantry and will design what to cook based on its knowledge about your health and preferences. Big Data for food has arrived.

Where does that leave grocery stores and restaurants? Many will be left out of this new food landscape, while others will get smaller and prepare food for delivery services. Still others will become experience centers, with more grocerants (restaurants in grocery stores) where you select your ingredients and the grocery store chef cooks it for you to eat in the store. Grocery stores, themselves smarter because of all the customer data they now own, will be fulfillment centers, some modeled after Amazon, and many integrated into Amazon’s platform.

Because your kitchen will be so smart, it will become a commerce center. You will shop from home, with tools such as augmented and virtual reality that give the sensation of being at the store. You will smell and touch what you buy, without the headache of parking or standing in a checkout line.

Perhaps these new kitchens will be maker spaces, educational centers that will teach us how to cook, what to cook and inspire us to tell stories around our food making. We’ll be content makers for a new media — food — a far cry from the static food photos we post on Instagram. We’ll stream our cooking experiences in our kitchens.

And who really likes to peel potatoes or chop onions? Food printers now produce fresh food from organic ingredients, freeze-dried and pulverized. The Last Mile is now no mile at all.

Kitchens, grocery stores and restaurants will be hubs for innovation. The engineers and designers at Bosch, GE, Kenmore and Siemens are fiddling with a whole new world in our former kitchens. Appliance makers have become hardware and software companies. Grocery stores and restaurants will fill new roles as they adapt to these new “platforms,” as our kitchen counters and frying pans will come to be known.

We might miss the joy of cooking. Or the satisfaction of making. Or the delight of creativity and the unexpected. Where along the road of automation will we pause? As our kitchens change into service centers that defrost and heat food delivered to our home, will we yearn for the temperamental toaster?

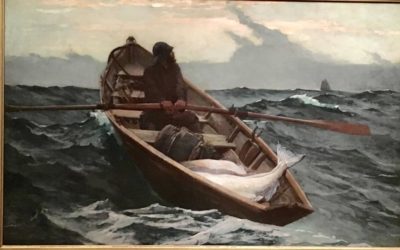

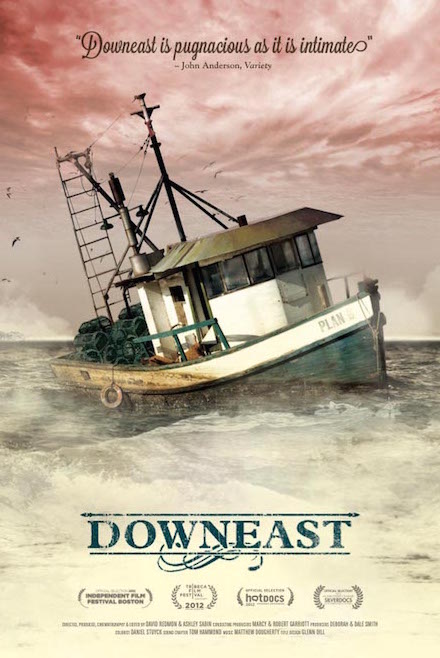

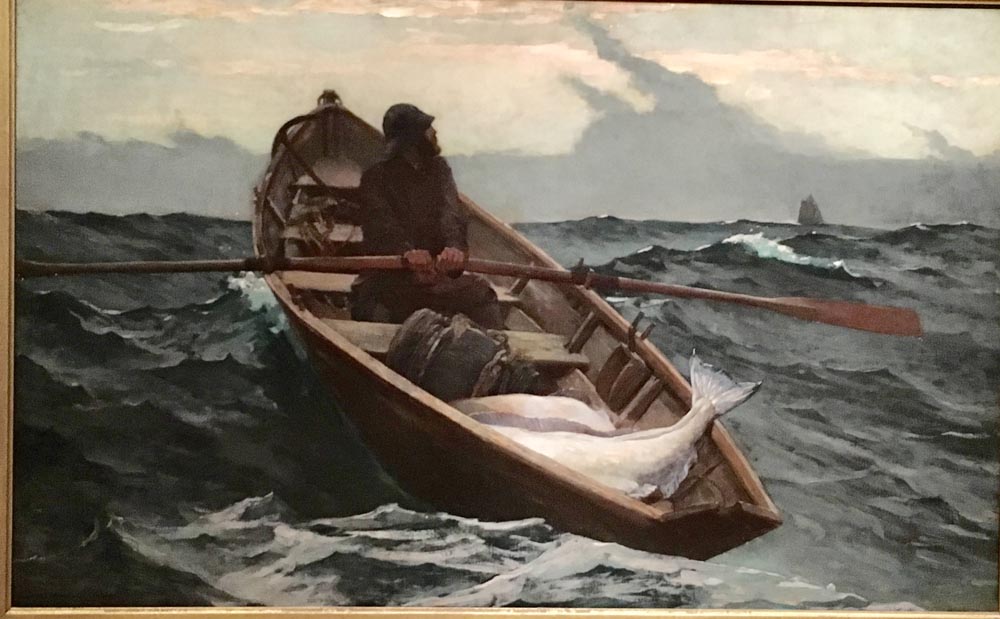

Food for Thought: South End Grocery

Dody and Steve Hiller are “mom and pop” of a small grocery store in Rockland, Maine, a fishing village turned tourist town. Fishermen still live and work there, but a few decades ago the town looked toward its art community for income and began shedding its image as a working waterfront.

South End Grocery has endured these changes, competing with modern mega-markets and maintaining a close connection with its community. The store thrives in a city whose 7,000 year-round residents have an annual median income of just $30,000, despite its new persona as an arty destination.

On a steamy summer day, customers form a long line at the lone cash register. The Hillers’ store is the third-largest grocery store in Rockland behind Shaw’s and Hannaford’s, two big supermarket chains. Despite its competitors’ being so large, South End seems to carry much of what they do — and more. You can find baseball memorabilia in one case, aisles lined with beer-packed coolers that share space with bananas and a bustling deli at the back of the store.

A bright blue runner leads customers through its single doorway, in which one often finds a community volunteer, raising funds for the animal shelter or a bereaved family that just lost a child to cancer. Sharing their space is one way the Hillers maintain a connection with their customers, about 75 percent of whom are fishermen. When the economy crashed in 2008, the Hillers saw fishermen struggle to make ends meet and decided to address their needs, seeking lower-priced products whenever possible.

Dody runs the deli area, which is responsible for 60 percent of their revenue, preparing meatball sandwiches and breakfast sausages. Son Shawn manages the bookkeeping and tech side of the business and boasts an impressive knowledge of local craft beers, which may be the reason South End is the top seller of beer kegs in the region.

Steve is the logistics guy, always calculating how much to order and when, then figuring out where to store it. He’s always on hand to meet vendors and distributors who pull up outside. In fact, if truck drivers roll into town too early to deliver their loads at Shaw’s, they rumble down to South End, where Doty greets them with hot coffee.

When a Walmart store came to the area a few years ago, the Hillers thought their store might be threatened. But their business recovered and carried on as usual, holding steady every year since then. Their biggest fear is the arrival of a Dollar General Store. Chances are, though, it won’t come with its own mom and pop.

Dody Hiller (center) at South End Grocery, the small supermarket in Rockland, Maine, that she owns with her husband, Steve (left), pictured with their son, Shawn (right). For more than 20 years, the Hillers have served their waterfront community, weathering the changes that have seen Rockland transform from a fishing village to an arty destination.

Food Movers: Confessions of an Instacart Shopper

He’s standing near the fresh herbs, staring at a forest of tiny green bundles, scratching his head, looking up and down from his phone. I offer some help, and he asks, “Where’s the basil?” After I help him choose a perky bunch, he thanks me and mumbles, “I hate shopping for vegetarians.” He’s wearing a shirt emblazoned with the Instacart logo.

Twenty minutes later I’m back in the produce section, and the man is still staring at herbs, looking defeated. “She wants fresh sage, not dried sage. What is it with these vegetarians?” he grumbles. In his defense, none of the herbs are labeled. I point out the fresh sage and wish him luck.

Those increasingly ubiquitous personal grocery shoppers roaming the aisles at a supermarket near you are paid a per-order bonus in addition to the minimum wage they earn per hour. The more orders they can complete in an hour, the more money they can make. But when they can’t find the right fresh herbs, like the shopper I encountered, their slowed quest results in fewer completed orders that day: in other words, money left on the table.

“If you do enough orders in a day and you’re really fast, you can make a lot of money,” explains a different Instacart shopper nearby.

Personal food shopping services have grown by leaps and bounds in the last few years. In Austin alone, six companies offer a range of personal shopping and delivery services at more than 10 stores. Nielsen’s Food Marketing Institute predicts that by 2025, 70 percent of consumers will be purchasing consumer packaged goods online. According to One Click Retail, Amazon already holds 18 percent of all online grocery sales.

That said, grocery shopping can be deeply personal. Customers have habits, preferences and quirks that retailers must accommodate with their third-party hand-picking-produce abilities.

“Ask anyone at HEB if they’ve had to find tahini and they’ll tell you, yes, it’s the hardest thing to find, and everyone wants it.”

As one shopper explains, “The people at Whole Foods are, well, ‘Whole Foodsie,’ ordering $50 jars of honey” and giving picky instructions about their produce. Because of this fastidiousness, online grocers started out offering only consumer packaged goods — pantry items like rice, beverages and breakfast cereals. But lately, most businesses have developed strategies for also offering fresh produce.

Still, online grocery shopping has room to grow. Less than 10 percent of customers in North America buy their fresh groceries online, according to Nielsen. Companies like Instacart have developed technologies that enable customers and shoppers to communicate as the shopper moves through the store. It’s a handy way to reassure customers that they’re getting exactly what they want. But shoppers may find their flow disrupted by picky comments such as, “Can you make sure to get the salmon that’s fourth from the back with the horizontal grill marks?” Or more frustrating: “I’m allergic to that brand.” Customer demands can get extreme, and shoppers feel the need to be polite even as they try to round up everything on their list.

Each company operates slightly differently for shoppers, who tend to stick to one company and one unique store. One exception is Burpy, which operates like the Uber of grocery delivery. Burpy shoppers may fulfill one order with products from a variety of stores. Shoppers are also paid differently depending on the company, ranging from minimum wage with bonuses per order, to flat hourly rates, to tips only. Shoppers generally work flexible schedules, which makes it an attractive second job or a good fit for students.

Regardless of payment criteria, speed matters. Shoppers create efficient strategies for moving through stores. Texas regional grocer HEB even has a digital platform that sorts a customer’s order according to the store’s unique layout, creating a “perfect workflow.” But despite deep store experience and superior technology, some items are still elusive to shoppers.

“Tahini,” one shopper says. “I’ve worked at five HEBs, and every time it’s a wild goose chase. I think it likes to hide itself. Ask anyone at HEB if they’ve had to find tahini and they’ll tell you, yes, it’s the hardest thing to find, and everyone wants it.”

Even when shoppers find everything on the list, customers must still get the groceries home. Because customers see only an itemized list, they often don’t realize how large their order is — an especially risky scenario when it’s for a pickup service or orders from Costco. Sizable orders of bottled beverages pose serious challenges.

“They pull up, and we’re dragging out three carts of groceries, two of which are full of bottled water, and they pull up in a VW Bug,” complains an HEB Curbside shopper. Amazon Fresh shoppers experience the same problem: “People will order 40 boxes of La Croix seltzer, and it’s crazy! You need eight shopping carts and that’s a lot of work.”

Despite the interconnected relationship between shopper and customer, an interesting disconnect remains. Shoppers frequently work in stores in which they do not personally shop, and often shoppers are asked to select items out of their comfort zone, like fresh herbs or fine wine. It begs the question: Can personal shoppers overcome these barriers to make this platform the future bread and butter of grocery shopping?

Food Movers: Paper or Plastic

The plastic grocery bag as we know it today comes from Sweden. Working for a plastics company called Celloplast in 1965, engineer Sten Gustaf Thulin developed a technique for sealing a folded tube of plastic and punching out a hole to create sturdy handles.

The polyethylene bag was waterproof, less likely to tear than paper, cheap to make and light to ship — and so cheap that stores have been giving them away since Day 1. Alas, they are so light that they blow into trees, fences and waterways with ease.

These single-use bags that revolutionized the retail world have now polarized it.

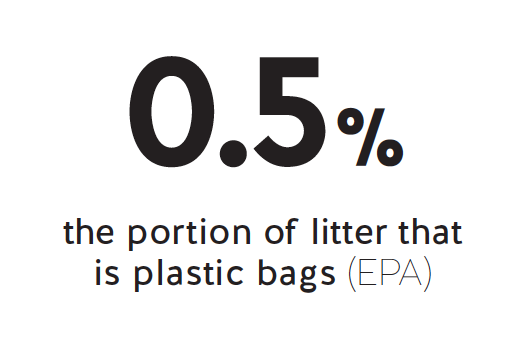

As one of the more visible forms of litter, plastics bags have over the past decade become the target of environmentalists around the world who advocate banning them. Some of the bag bans passed in cities such as Austin have been challenged by lobbyists and lawmakers who argue that plastic bags are more useful than they are harmful to the environment.

Even though bag bans in places like China and California have led customers to reduce all bag use by upwards of 70 percent, critics cite numerous studies that have found that manufacturing and shipping paper bags is two to three times more harmful to the environment than making and moving single-use plastic bags.

For example, a single truck can transport two million plastic bags, but it takes seven trucks to transport the same number of paper bags. That works out to five to seven times more cargo weight on both sides of the chain — i.e., coming to stores as new bags and transported in the waste stream — as well as added greenhouse gas emissions.

Scientists use what is called a life-cycle assessment to determine the global warming potential and environmental impact of how different kinds of bags are made, transported, used and recycled. The United Kingdom’s Environment Agency compared different kinds of bags for a life-cycle assessment study in 2011 and found that you’d have to use a paper bag four times for it to be more environmentally friendly than a standard single-use plastic bag. And what’s more surprising? A cotton bag would have to be used at least 173 times. In other words, because of the intensive resources used to make and manufacture cotton bags, you’d have to use a cloth reusable bag 173 times to have the same environmental impact as a single-use bag.

But there are other factors to consider in that study: Plastic bags are more toxic in aquatic environments, and they break down into micropieces; however, paper bags require more water, energy and chemicals to produce, which can be toxic to the environment during the manufacturing process.

As is often the case, the solution may not be a simple binary choice between paper or plastic. For example, in some countries with bans, such as Morocco, you’ll find flimsy recycled paper fiber bags that feel like soft fabric and are biodegradable, while Canada is leading efforts to create a recycling stream for existing polyethylene bags.

Even if the bag bans don’t last, the effort to use more sustainable, reusable packaging to move our food will continue. That requires changing consumers’ and retailers’ behavior, no small feat in the grocery business.

A cotton bag requires more resources to make and transport than a plastic bag. So many more, in fact, that you’d have to use it 173 times for it to be more environmentally friendly than a plastic bag. But, plastic bags are much more toxic to aquatic environments.

Food Movers: Keg Cycle

Few pieces of hardware are as synonymous with a good time as a keg. And while other carbonated fluids are stored in these aluminum or stainless steel tanks, when we hear the word keg, we think of one beverage: beer.

Nationwide, breweries opened at a rate of nearly three per day during 2017 — 997 in total — and each brewery has its own fleet of kegs. Each one of these vessels has a salmon-like lifecycle in which it leaves its homeland full of life and returns home depleted. Unlike a spent salmon, an empty keg can jump back in for another round. But like all too many migrating fish, many kegs never make it home. Of those 997 breweries that opened in 2017, 165 went belly up. For a company that’s barely covering its costs, keg loss can make the difference between a red or green bottom line for the year.

When a keg is filled at a brewery, it is ready to go out into the world and do its job dispensing beer to the people. A distributor facilitates its journey, which may include a retail outlet such as a bar, restaurant or liquor store — the first stop before its destination at a party by the lake or other #goodtimes. If all goes well, and everyone keeps their word, the empty keg will eventually return to its home brewery. If not, and the keg never makes it home, the brewery that owns it foots the bill.

An American-made stainless-steel keg can cost a brewery more than $100, and the average annual keg loss nationwide is about 6 percent, says Tim Cognata, business development director of the beer services company Satellite Logistics Group (SLG). This transformation from stainless steel to statistic ends up costing a lot more than the $30 deposit normally collected when the brewery lets a keg go. For a small brewer, he says, replacement costs for kegs can add up quickly and take a big bite out of the profit margin.

SLG offers a service called KegID, introduced in 2012, which uses scannable barcodes to keep track of a keg’s movements, including timestamps at various stops in the keg cycle and notes about maintenance and contents.

If a keg is not returned, services like KegID provide concrete data for tax-loss purposes. Even though breweries may lose more than 5 percent of its fleet of kegs, Cognata says, most breweries are writing off a mere 1 to 2 percent drop in keg numbers because they don’t have the documentation to prove greater losses. If breweries had tracking data for each keg, they could claim all of those lost vessels without worrying about facing a penalty for overclaiming, in the event of an audit.

The same data that allow a brewery to prove its loss to the IRS can also serve as evidence with which to confront a distributor for losing kegs. Sometimes a retailer collects a larger deposit than the brewery charges the retailer, which can be especially bad for keg recovery. Regardless of the reason a keg is lost, and whether or not it’s found, breweries are happy to be armed with the data KegID provides, says Cognata.

“KegID has an invoice function where you can bill a distributor for the residual value of a keg, minus the deposit,” Cognata explains. “Most distribution contracts state that the distributor is responsible for any lost assets. We provide the concrete data so that conversation can happen: ‘We sent you X number of kegs, and Y came back.’”

Thanks to that hard evidence, Cognata says, when distributors know a brewery partner uses KegID, kegs start coming back.

Other technologies are being deployed toward similar goals. A handful of well-to-do breweries are welding GPS transmitters to their kegs to track their every move — but it’s extremely expensive (think satellite phone versus cell phone). In 2009, New Belgium Brewery began attaching Radio Frequency Identification Devices (RFID) to its 100,000 kegs. RFID is a different way to keep track of information similar to what KegID stores.

“(RFID) lends itself to keeping track of whole pallets of cargo rather than individual kegs,” Cognata says. New Belgium has since moved from RFID to SLG’s tracking technology.

The ability to closely track these mobile assets adds up to big cost savings for brewers. Today, more than 200 breweries use KegID, from well-known national micro brands like Sierra Nevada to well-named niche labels like Moustache Brewing Company.

When the container is worth almost as much as the contents it holds, it pays to keep track.

Best Before… Who Knows?

Real food. It’s what everyone wants — farm fresh and chemical free. But real food spoils. In the field, on the truck, at the store and in your fridge. That’s why innovators and entrepreneurs are coming up with new and nifty ways to help prolong the life of food.

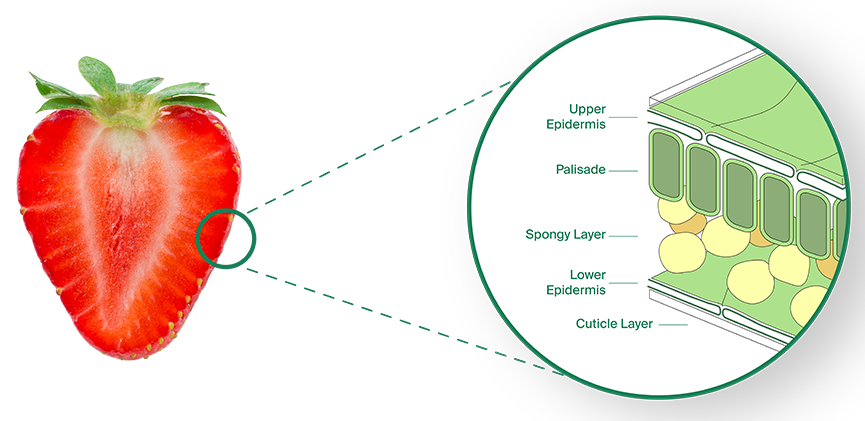

The next time you purchase perfectly heart-shaped strawberries on the East Coast, consider this: They were probably picked and packed into their plastic clamshells on a Central Valley farm in California between five and eight days ago.

They could have been harvested on a balmy 70-degree morning or in the 95-degree heat of mid-afternoon. Perhaps they sat in the field for one hour — or four. Maybe the pallets took five days to cross the country in a temperature-controlled trailer, or maybe the trailer refrigerator broke down halfway through the journey. Once at the store, the strawberries might have sat on the shelf for a day, or a few more. “Many things can impact shelf life,” says Kevin Payne, vice president of marketing at Zest Labs, a San Jose-based tech company trying to take the mystery out of produce shelf life. “But you can’t see those until the very end,” when 24 hours later, your picture-perfect ruby strawberries morph into camo-green fuzz balls.

Six dollars wasted. Dreams of strawberry shortcake vanished.

And now you can add that pound of trashed berries to the 400 pounds of food you personally waste each year. According to the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), 40 percent of food produced for human consumption in the United States goes uneaten. Just one-third of that wasted food could feed the 48 million Americans living in food-insecure households.

Wasted food is bad for humanity, but experts believe it could be even worse for the earth. Food waste is responsible for 16 percent of our country’s methane emissions — the pollution equivalent of driving 37 million cars per year. Growing, processing, transporting and disposing of food uses roughly 10 percent of the U.S.’ energy budget, 50 percent of our land and 80 percent of our fresh water consumption. So, when you figure 40 percent of that goes unused, that’s a lot of unnecessary pollution accelerating climate change.

In the developing world, most food waste occurs in the field or in transit due to poor infrastructure or lack of refrigeration. But in the U.S. and the rest of the developed world, the majority of food is wasted on the farm, at the supermarket and at home.

The food industry had mostly resigned itself to these inefficiencies. “The approach has been that waste is the cost of doing business,” Payne says. “And the solutions have historically been reactive.”

That’s all starting to change thanks to a shift in food culture, environmental awareness, technological advances and a host of entrepreneurs shaking up the industry through food-shelf-life innovations.

Polluting the Planet