Your Food: Up for Grabs?

Don’t panic, but your food is about to appear on your plate in surprising and unexpected ways.

More than ever, food delivery is becoming faster, fresher and more personal. Our food supply chain looks transitory as it shifts to accommodate changes in where our food comes from and where it’s going. The traditional food movers — large logistics, distribution and transportation companies — are now in the company of small, scrappy, food delivery services.

These changes are the result of the aggregation of big data and consumers who are willing to forego the shopping experience for the shipping experience. Both the data and the consumers who create that data have come together to transform our food supply chain. For the better, we think. Just about everything is up for grabs. Farmers look more like engineers, food is fresher and those who deliver our food are coming from unexpected directions.

This issue, our third, takes a close look at some of the shifts from imagination to reality. Food waste is a top concern now as consumers are either being shamed by the amount of food left on their plates or rallied to find new ways to use food waste. If we accept the fact that we can’t eliminate the waste in our supply chain, we can turn our attention to ways we can put it to use, either as a source of energy or repurposed as new food or non-food products. Ari LeVaux takes us to the land of biodigesters and ugly fruit jam. Jen Wong offers surprising ways in which food waste reappears in new shapes and forms, such as coconut shell tiles.

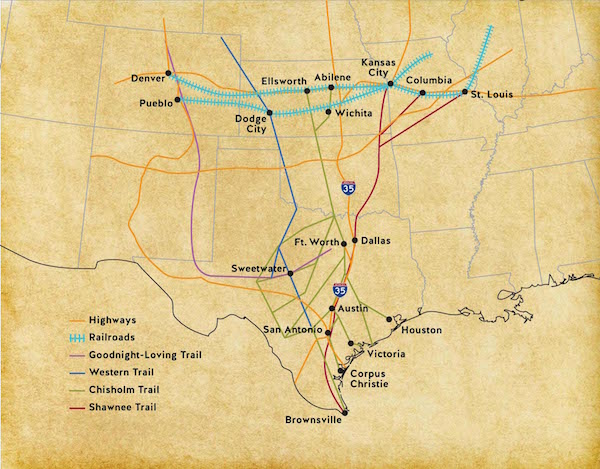

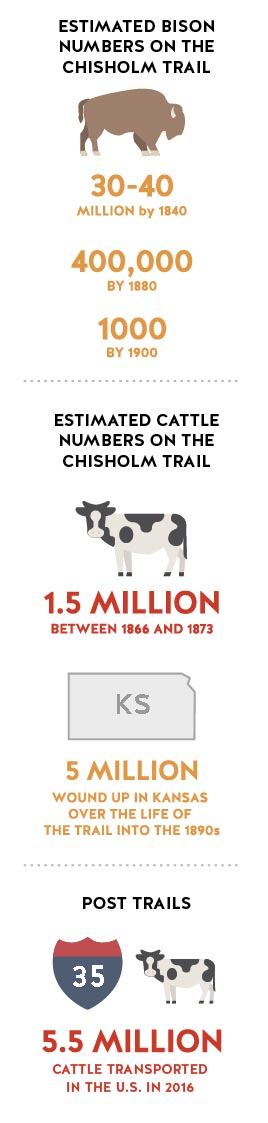

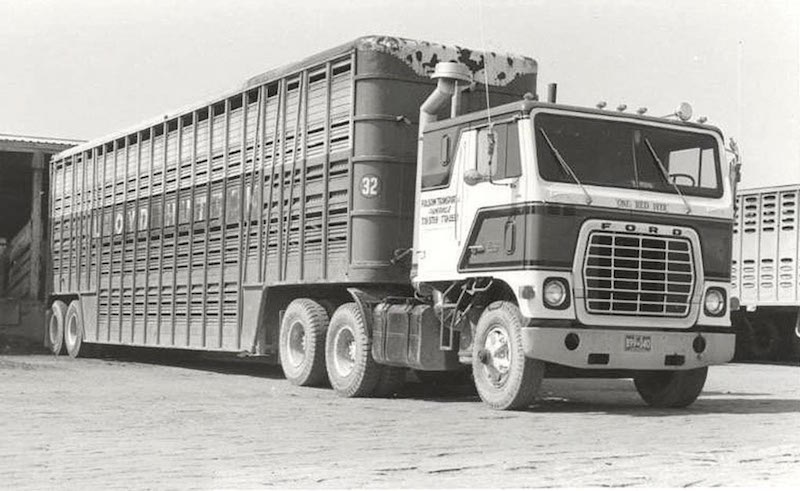

When two Norwegian shipping firms, Yarrao and Kongsberg Gruppe, announced their electric, driverless ships, the prospect of a global food supply chain that doesn’t require bunker fuel (the lowest grade of fossil fuel) suggests we may soon see more sustainable ways to ship food around the world. Providing context for this new model for shipping food is our story about canals and barges, the original slow movers of food along inland waterways. David Leftwich shares his story of barges that travel up and down the Mississippi in this moment of battery-powered cargo. And Jeannette Vaught’s history of cattle logistics reminds us that the tracks of our food have been visible on our landscape for centuries.

The Norwegian vessels also promise robot loading and unloading of cargo, one of the many human displacements occurring within our food supply chain. Rachel Wharton’s story about robots and Melanie Haupt’s images of vending machines that serve us our food suggest that the experience of eating may lose its deeply human connection.

To give us some perspective of how we got here, Laurie Zapalac explains how a mundane container of food was invented because of a challenge prize offered by Napoleon in the late 19th century. Cans today are smarter, carrying much more than food. They carry the history of their contents, and some contain sensors for tracking and tracing a can throughout the supply chain. Zapalac sheds light on how we’re getting a better view of a more transparent food supply chain.

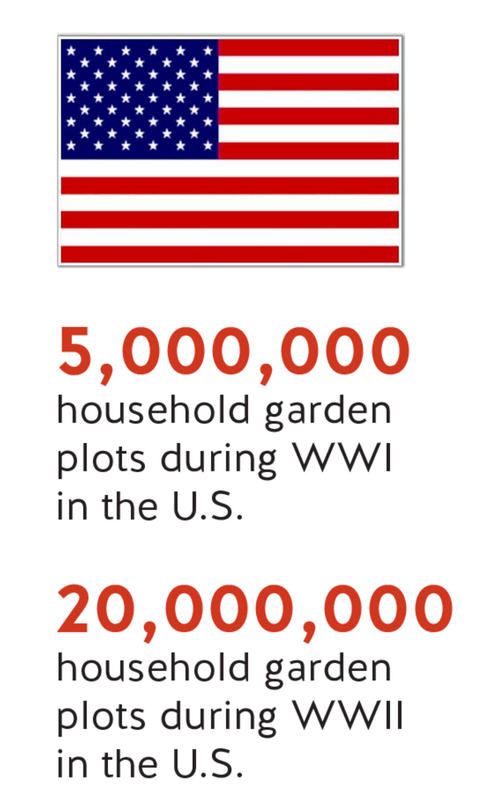

Jane Black’s story about urban agriculture tells us more about the complexities and questions that accompany this new way to feed cities. And if you thought urban agriculture was the way to create Smart Cities, read Gergely Baics’ story about a 19th-century smart city. Cory Leahy’s deconstruction of wartime cookbooks on ration use brings new meaning to ways we might attack the food waste problem.

We do our part to help change how we feed our cities through our annual Food+City Challenge Prize. Each year we see more and more startups that are finding ways to improve food logistics. See our description of what these startups are doing to get food faster and fresher to our cities. And finally, check out our recommendations for cool books and nerdy websites.

Chisholm Trail

Chisholm Trail

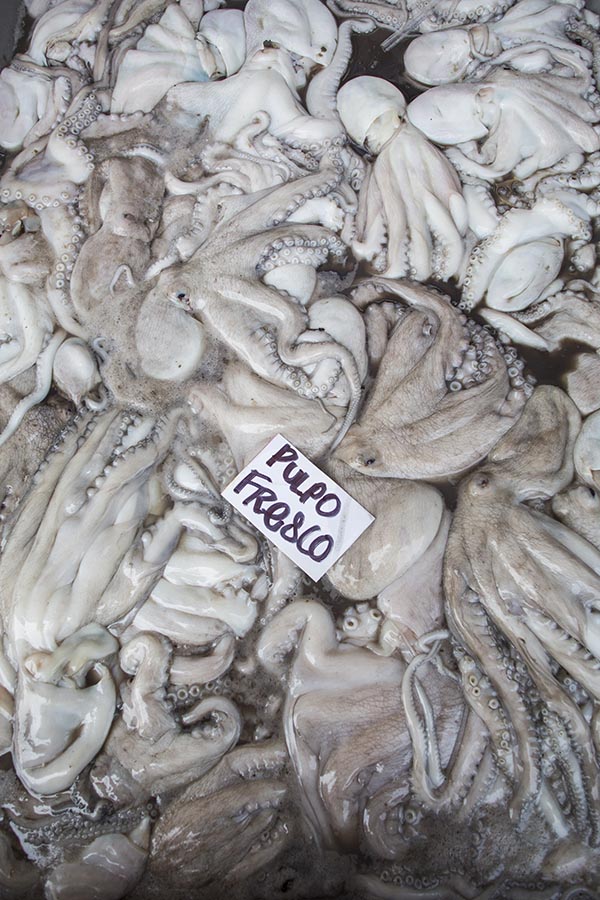

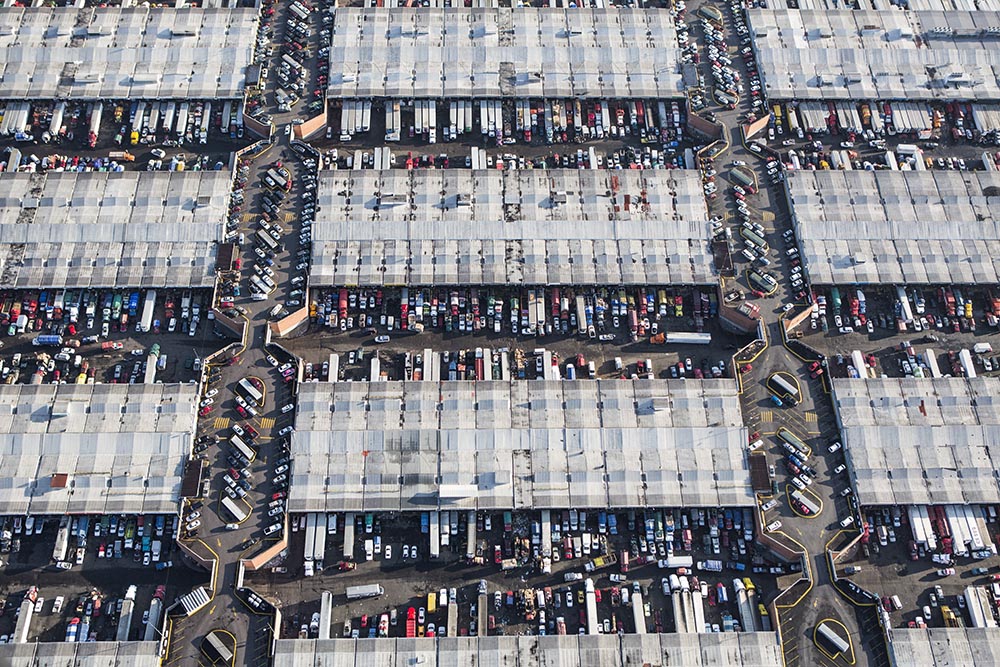

Feeding a city of 21 million inhabitants is no easy task, which is why this market has its own zip code, an independent governing body and even its own 700-man police force, which comes in handy considering more than $9 billion changes hands annually, mostly in cash. This makes Central de Abasto one of the largest economic centers of operations in the country, second only to the Mexican Stock Exchange.

Feeding a city of 21 million inhabitants is no easy task, which is why this market has its own zip code, an independent governing body and even its own 700-man police force, which comes in handy considering more than $9 billion changes hands annually, mostly in cash. This makes Central de Abasto one of the largest economic centers of operations in the country, second only to the Mexican Stock Exchange.